For the first time in half a decade, Coloradans may engage in debate next year about what the state’s transportation funding priorities should be, as backers of a ballot initiative to boost road funding received approval this week for the titles of three potential measures.

While supporters must figure out which of the proposals they want to push, each shares a central theme: Moving revenue from various transportation fees away from transit, bike lanes and electric-vehicle infrastructure to road construction and maintenance instead. In addition, the proposals float the idea of diverting two-thirds of state sales-tax revenue generated from auto-related sales — vehicles, auto parts and tires — to road construction, resulting in a boost of $700 million to $800 million per year.

A still-forming coalition led by the Colorado Contractors Association saw a convergence of problems and felt like it had to act now, CCA Executive Director Tony Milo said in an interview. Congestion is increasing and road-pavement conditions have become some of the worst in the country, according to studies. Meanwhile, state legislators focus transportation funding, including much of which was passed in 2021 law, on non-road fixes such as buses, charging stations and bike paths, he said.

“We’re just at a breaking point, honestly. And there’s no plan to make it better,” said Milo, whose organization represents the companies that build and repair most of Colorado’s roadways. “We’ve got to do something because the General Assembly certainly isn’t stepping up to do it. Our members are not only worried about their businesses, but they’re worried about all businesses and the quality of life in Colorado.”

Colorado’s troubled highways

The proposal already is drawing opposition from environmental organizations worried that it would pull the rug out from under state funding for means of transportation that must increase for Colorado to reduce transportation-sector emissions. And the initiative, which could land on the 2026 statewide ballot, comes as several groups already are telling legislators that the state needs to reduce spending on highways and boost investment in transit and other multi-modal options.

Origins of this initiative lie in frustration with Senate Bill 21-260, a $5.3 billion law that created new fees on retail deliveries, Uber and Lyft rides, rental cars and gas sales to fund transportation. However, except for the gas fee, most of that new revenue goes into four different enterprises that in turn fund vehicle-electrification efforts, transit and connectivity efforts like bike lanes and sidewalks more than highway fixes.

Meanwhile, Colorado’s long-deteriorating roads are getting worse. An annual Reason Foundation report released in March ranked the state’s highways 43rd overall in cost-effectiveness and condition. Some of the notable sub-rankings: Colorado is 47th for rural pavement conditions, 45th for urban pavement conditions, 40th for urban fatality rate and 36th for congestion, which costs state residents 36 extra hours a year in traffic.

The amount of money that Colorado puts toward road maintenance and expansion is a debated number. The Colorado Department of Transportation’s current budget puts about $1 billion toward asset management, while Milo said the amount going specifically to roads is likely closer to $800 million. But the ballot initiative could nearly double that total either way — a shift Milo called “life-changing.”

How the road funding would work

The biggest road-funding boost that the ballot effort would enact would be through its diversion of auto-related sales-tax revenues, which now go into the general fund to be used in any way the Legislature determines. That would account for about $700 million in the increase in roadway funding, while the transfers of money out of the newly formed enterprises and into the State Highway Fund would make up another $100 million or so.

Supporters have floated several versions of the initiative so far. One has a 10-year sunset. Another adds roadway engineering and the Colorado State Patrol to the list of recipients for the redirected funding. Still another wouldn’t touch the enterprises at all but just would seek to direct two-thirds of auto-sales-tax revenues toward roads.

Even before backers figure out the specifics, though, they are emphasizing that Colorado’s deteriorating roads are hurting the state’s economy in numerous ways. They are slowing the movement of goods to market and people to their jobs, while they are making commutes more dangerous, Milo said.

Road funding was issue this legislative session

Legislators balanced the 2025-26 fiscal-year budget in part by cutting about $110 million that was set to go to construction and maintenance this year. A coalition of business organizations and public officials wrote the Joint Budget Committee in March and argued that when CDOT itself has said it’s short $350 million in what it needs for annual highway upkeep, legislators must invest in pavement rather than just in emissions-cutting moves.

“We cannot mass-transit our way out of this hole. The state’s backbone is made of roads, bridges and highways,” the letter read. “In some specific urban areas, multimodal and mass transit systems may work – although even Denver has seen a decline in RTD use – but they are created at the expense of critical investments around the state, especially in rural areas and smaller municipalities with expansive land areas and diverse topographies.”

That letter captured the essence of the debate that is set to ramp up around the proposed ballot initiatives.

Environmental groups push back

At Wednesday’s hearing before the Title-Setting Board, attorney Martha Tierney, representing a Conservation Colorado leader, argued the proposed ballot title was misleading because it didn’t explain from where the new road funding was coming. She successfully persuaded the board to add a clause to the ballot question saying that that the funding includes “some revenue currently allocated for other transit-related purposes” to explain that boosting road funding may cut bus or train funding

“Voters would surely be surprised to learn that they inadvertently passed a road-funding measure that also significantly defunds a number of programs that are currently being funded,” Tierney said. “This is the classic coiled-up-in-the-folds measure where voters will be misled and will not understand what they are voting on.”

Last month, several organizations went before the Transportation Legislation Review Committee and made the opposite argument of Milo — that the state is putting too much funding toward roads and not enough into multimodal transportation.

Matt Frommer, transportation and land-use policy manager for the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project, noted that of the $11.3 billion designated for future expenditures in CDOT’s 10-year plan, just $473 million is earmarked specifically for transit. While $2 billion of the total could got to building highways with transit lanes, a comparative $905 million is set for expansion of Interstate 70 in the Floyd Hill area and $415 million for expansion of Interstate 25 north of Denver, he said.

Will more lane miles equal more pollution?

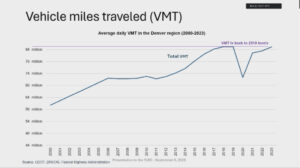

Meanwhile, although the Denver Regional Council of Governments has set a goal to reduce the amount of vehicle miles traveled daily, the number of miles covered by cars and trucks in Colorado had exceeded pre-pandemic levels by 2023, leading to increased congestion. And the roughly 85 million vehicle miles traveled per year by cars in this state could grow to 121 million by 2050 unless residents are given other ways to travel around, Regional Air Quality Council Executive Director Mike Silverstein told the TLRC at its Sept. 8 meeting.

This graphic from the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project, shown at the Sept. 8 Transportation Legislation Review Committee, shows the rise in vehicle miles traveled in Colorado over the past quarter-century.

“Colorado’s transportation system faces major challenges,” Frommer said. “Current funding does not match our environmental goals.”

Yet the free-market Common Sense Institute points to those same statistics and says they show the need for more investment in roads. In a March report, transportation fellow Ben Stein noted that vehicle miles traveled in Colorado rose 25% between 2001 and 2017, yet lane miles rose less than 2% — a factor that has led to deteriorating road conditions particularly as so much transportation funding goes to other uses.

“The significance of this shift is hard to understate,” Stein wrote. “The state now takes transportation-related fees and directs them toward environmental mitigation, mass transit and demand-management efforts rather than infrastructure.”

What is next in road funding debate

Voters rejected a sales-tax hike for roadway construction in 2018 and then defeated a revenue-retention measure in 2019 that sought to keep tax refunds and put them in no small part toward roads. Post-election polling done by groups like Milo’s found that it wasn’t that voters didn’t want to fund roads but rather that they felt they paid enough in taxes and wanted the state to use that money to fix highways, the CCA leader said.

No major increase in federal funding is likely on its way soon. At a Sept. 25 discussion organized by advocacy group Move Colorado, Ward McCarragher, American Public Transit Association vice president of government affairs and advocacy, noted that one-time backers of a federal gas-tax hike no longer see it as a viable solution and that a long-discussed vehicle-miles-traveled fee remains stuck in neutral.

So, if more money is going to Colorado highways, the proposed ballot measures may be the only option.

Unlike a progressive-income-tax measure that hit a stumbling block this week as backers sought to get a title for it, the transportation measures have a path forward, and supporters will soon be able to begin collecting signatures. They must decide on the details of their ask to voters, but the tone of the debate is being framed already.