Colorado regulators gave preliminary approval Thursday to the state’s first comprehensive rules on carbon capture and sequestration — stringent rules that business leaders warn could scare off projects that are needed to meet statewide emissions-reduction goals.

The rules that Colorado Energy and Carbon Management Commission leaders are set to give final approval to on Dec. 11 will be included in the state’s application to take regulatory primacy for the growing sector from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. They would establish safeguards that ensure the safety of Class VI injection wells and limit the impact they can have on surrounding communities.

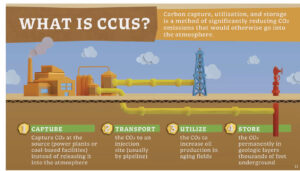

Operators of such wells sequester carbon coming from industrial sites — typically oil-and-gas drilling pads or other industrial facilities whose emissions otherwise are hard to limit — and then inject them permanently into geologic layers thousands of feet underground. The sector, prominent in a handful of other states, is new to Colorado but is considered essential to the state reaching its goal of net-zero emissions by 2050.

“The state is unlikely to achieve net-zero without carbon management,” said Michael Turner, senior director of strategic initiatives and finance for the Colorado Energy Office, during the first day of the rulemaking hearing on Monday. He added Colorado has enough geologic space to hold 134 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide underground, indicating “enormous opportunity for the state to lead in the carbon-management industry.”

Will investment go outside Colorado instead?

A graphic created by the University of Wyoming Center for Geology Research explains carbon capture and underground storage.

Carbon-management companies, including those associated with large oil-and-gas producers and other industrial firms, have indicated they are willing to build carbon-sequestration projects in Colorado.

But many said that if Colorado rules make it infeasible to build here, they’re likely to invest instead in states like Wyoming, Texas or Louisiana — using significant tax credits being offered by the federal government. That not only would cancel a potential new economic sector but would make it hard for some plants to cut emissions without cutting production.

And after the five ECMC members appeared to coalesce around final rules on Thursday, several business leaders said those regulations could make it so difficult to guarantee approval of permits by the state that many operators likely won’t spend resources even trying to meet them.

“If you look at other states with easier rules, people will spend their dollars there,” warned Christy Woodward, regulatory affairs advisor for the Colorado Chamber of Commerce.

How regulations on carbon management would work

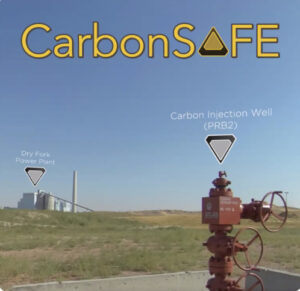

A photo used by a University of Wyoming official in his presentation to the Colorado Energy and Carbon Management Commission shows the size of a Class VI wellhead and its proximity to a an industrial facillity.

That may be a welcome sentiment to a handful of environmental organizations who, while seeking stricter regulations from the ECMC, also said they believe the technology is “dangerous” and a distraction from proven carbon-reduction strategies, as Wild Earth Guardians attorney Katherine Merlin told the ECMC.

“This is not something we’re holistically in favor of,” added Ean Thomas Tafoya, state director for GreenLatinos, about carbon sequestration.

Under the proposed rules, operators would apply to the ECMC for drilling permits and then undergo an 18-month technical review of their plans focused on their siting, equipment and impact on surrounding communities. Then, if they are approved for a permit to drill, they still would have to get a second permit before they begin injecting the pressurized carbon dioxide based on site-specific data that they’d be required to provide to the ECMC.

Those requirements are not dissimilar to current demands from the EPA, which operators sought through a bill to take primacy from in order to let the state rather than the federal government control the process. In fact, two-thirds of the proposed regulations are copied from EPA rules. It’s the one-third of stricter rules, which business leaders say don’t exist in that depth in any other state, that give operators great concern.

Restrictions on proposed Class VI wells

Legislators in House Bill 1346 required a hard 2,000-foot setback between Class VI wells and homes, schools and commercial buildings — the same setback as that which is required of oil-and-gas wells, but with no potential exemptions like oil-and-gas rules allow.

Colorado state Rep. Gabe Evans questions Reps. Karen McCormick and Brianna Titone in April about their carbon-capture bill.

The agreed-upon rules also require financial assurances from operators that can run into the tens of millions of dollars, compliance with local-government siting plans and requirements like submission of development plans that mirror oil-and-gas rules. Colorado Department of Natural Resources leaders also hope to run a bill in 2025 to create a state enterprise to monitor Class VI wells after their closure, funding it via a fee on the operators of those wells, said Aaron Ray, DNR assistant director for energy innovation.

Operators’ biggest holdup, however, is a requirement they have no negative net impacts on disproportionately impacted communities — those that are poorer or have larger percentages of minority residents — when wells are within a half mile of homes or schools. While arguing that this could be financially burdensome, they felt at the start of the hearing that they still could fall back on statute that lets the ECMC consider beneficial cumulative impacts of projects when assessing applicants, including economic impacts of jobs or infrastructure improvements.

But on Thursday, ECMC members said they intend to consider negative and beneficial impacts only regarding public health and environment and not regarding economics. That also would nix the possibility of considering how such projects could help negative impacts to a community if, say, cement or manufacturing plants were to have to shut down because they couldn’t employ carbon management to lower their emissions.

“Colorado is closed to CCS projects”

And the commission went further and said staff could not consider as a benefit the social cost of carbon that would be removed from the air by the wells, despite other state rules that measure social cost of carbon in assessing potential fees on industrial facilities.

Without such allowances, companies that might consider investing millions of dollars in such wells will hesitate, not knowing if they have a viable path to permit approval without the ECMC being able to consider potential beneficial impacts, business leaders said. While the carbon footprint of Class VI wells is exponentially lower than that of oil-and-gas wells — they emit no nitrous oxide, require no storage tanks and don’t attract truck traffic — there is almost no way under the rules to offset even the smaller negative impacts they would have.

“We remain concerned that this will be a sign to companies that Colorado is closed to CCS projects,” warned John Jacus, a Davis Graham attorney representing Carbon Storage Solutions, which is building a Class VI well for Front Range Energy near Windsor. “We simply want you to adjust the process and procedures to give the CCS industry a level plane with neighboring states as much as possible … Simply adding to already stringent regulations at the behest of those openly hostile to carbon management — and, therefore, opposed to federal and state policy —is not warranted.”

John Jacus is a partner at Davis Graham & Stubbs.

How rules could affect goals for carbon reduction

Beyond failing to attract projects that Gov. Jared Polis has touted, the inability to offer carbon management as an emissions-cutting strategy could leave some manufacturers in hard-to-decarbonize industries struggling to meet emissions-intensity goals. Without that option, some may be forced to cut production, meaning layoffs in communities that already are economically challenged or, at worst, potential out-of-state relocation of work for national companies with plants in states friendlier to carbon management, business leaders said.

Peter Omasta, climate action manager for cement manufacturer GCC Pueblo, noted his company has cut its emissions intensity more than 16% since 2015 but still must do more despite facing a high cost to build a full-scale carbon-capture system. If the regulations drive the cost up more, particularly if the company must build a pipeline spur at a cost of $2 million per mile to get wells outside of a DIC, it could have to move production elsewhere, which could cause manufacturers to have to ship cement in from outside the state or country in a way that would increase the carbon footprint of that product.

“If there is too stringent a regulation, too high a cost … you’re going to have less of this technology,” Omasta told the ECMC.

Environmental groups also fell short with several requests to the ECMC.

Matt Sura, an attorney for Larimer County and Longmont, argued the requirement to assess no negative net impacts should extend from a half mile from structures in DICs to any well within a mile of a DIC. ECMC members resisted this request, though with roughly 48% of Colorado being considered a DIC — often because of the lower incomes of residents in rural areas without pollution problems — the mandate still cuts a lot of the state off from easy access to Class VI wells.

More details about rules on carbon management

A head for a Class VI well is shown behind the green fencing on the Windsor-area property of ethanol producer Front Range Energy.

Several groups also asked commissioners to take into account in their cumulative-impact analyses the environmental impacts of the pipelines connecting the wells to underground storage, citing accidents elsewhere that have spilled carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. However, as the ECMC does not have jurisdiction over pipelines, commissioners said they could not consider that.

Meanwhile, industry leaders won one small victory in the rulemaking. ECMC leaders agreed commercial buildings co-located on companies’ industrial sites are not violations of the 2,000-foot setback — a ruling that will let Carbon Storage Solutions continue to build its Windsor-area project, the first such Class VI well in the state, under EPA supervision. The EPA is not likely to make a decision on giving Colorado regulatory primacy over such wells until early 2026, officials have said.

If the ECMC approves final rules as expected, however, only time will offer proof as to whether the new regulations allow for the carbon-management sector to flourish in Colorado as it does in some other states or whether they will stifle potential growth.

“Do the draft rules as proposed meet the statutory directive to reduce economywide greenhouse gas emissions?” asked Courtney Shepard, a Greenberg Traurig shareholder representing the Colorado Chamber, before answering her own question. “Companies won’t take the extra time and expense to permit in Colorado when they can go to states that have just adopted EPA rules.”