When the House Judiciary Committee conducts that chamber’s first hearing Tuesday on a bill to redefine harassment in state law, business groups won’t be rallying around it.

But they also are unlikely to put up anywhere near the level of fight they exerted when Senate Bill 172 — the Protecting Opportunities and Workers’ Rights (POWR) Act — got introduced in late February. That’s because a series of amendments made over the past two weeks in a Senate committee and on the floor of the Senate has made the proposal, in the opinions of several groups, a much better bill.

To be sure, SB 172 still takes Colorado into territory where only three other states have wandered, jettisoning the long-accepted legal standard of harassment as an action that must be “severe or pervasive.” It replaces it with a requirement that the action be “subjectively offensive to the individual alleging harassment and is reasonably offensive to an individual who is a member of the same protected class,” and that it not constitute just “petty slights, minor annoyances and lack of good manners.”

Other POWR Act provisions

The bill also strengthens protections for workers with disabilities, a provision that business groups did not fight. And it tightens employers’ abilities to use non-disclosure agreements as parts of harassment-claim settlements with workers, a provision that, while certainly more restrictive, was not a lynchpin of employers’ opposition.

The bill also tightens what employers must do to claim an affirmative defense, in which one can introduce facts that justify their conduct. And it is that section of the bill, in addition to the definition, that has undergone significant change under lobbying from business groups, local-government organizations and public universities and colleges.

A panel featuring (L to R) Special District Association of Colorado General Counsel Diane Criswell, Sherman & Howard Attorney Brooke Colaizzi, Special District Association Executive Director Ann Terry and Colorado Chamber of Commerce President/CEO Loren Furman testifies against the POWR Act before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

One amendment that was added during Senate debate last week, for example, removed the requirement that employers must keep records of all oral complaints made to them by workers in order to state an affirmative defense. That added to another change that said that employers must keep a record repository of complaints but that such a repository no longer would be tied to the affirmative defense, making such a defense easier to claim.

A separate Senate amendment broadened the availability of the affirmative defense such that an employer could claim such a defense if it can show that it took action to investigate or address any complaint it had received from workers. And an amendment that was added in the Senate Judiciary Committee removed a requirement, considered particularly onerous by business groups, that employers could not claim an affirmative defense if they’d had a single complaint filed against them by an employee in the past five years.

What the changes mean

Taken in whole, the series of changes transformed a bill that organizations like the Colorado Chamber of Commerce and Special District Association of Colorado had predicted would open a floodgate of new lawsuits and made it into one that’s more likely just to require stricter compliance. The narrowing of the new definition of harassment — the first version of SB 172 broadly declared it as anything “offensive to a reasonable person in the same actual or perceived protected class” — also should keep away most frivolous suits, though not necessarily single acts that are harder to prosecute under the “severe or pervasive” definition.

Co-sponsoring Sen. Faith Winter, the Westminster Democrat who introduced a further-reaching POWR Act in 2021 only to see it die in the House that year, said her goal has been to widen the protections of the law to ensure those worst incidents — single or repeated — are violations. She cited decisions in which rape or the use of the “n-word” did not meet a particular court’s definition of harassment — sometimes due to extenuating circumstances, proponents noted — and said Colorado must lead the way to make enforcement of the law more inclusive.

Colorado state Sen. Faith Winter speaks on the Senate floor for the POWR Act she is co-sponsoring.

“We want to ensure that every single person in Colorado who shows up to work feels safe,” Winter said during debate in the Senate on Wednesday night. “And that is what this bill does.”

Some opposition to POWR Act remains

Republicans — who voted as a bloc against the bill, which passed the Senate 23-12 on the strength of full Democratic support — acknowledged that the bill improved significantly since its introduction. But Senate Minority Leader Paul Lundeen, R-Monument, said elements like the move away from a definition of harassment currently used by 46 other states still leave them troubled, particularly regarding what legal actions could come from the broader boundaries placed on the term.

“This is a sea change, if you will, in the law of harassment and discrimination in Colorado,” added Assistant Senate Minority Leader Bob Gardner, R-Colorado Springs. “It is unnecessary.”

One other action of note softened the fears of opponents toward the impact of the bill, though it didn’t come through any sort of amendment.

EEOC flap

In testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Aubrey Elenis, director of the Colorado Civil Rights Division, said that the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission informed her that the federal organization would terminate its contract with the CCRD to investigate dual-filed cases if the Legislature changed the definition of harassment. That, Gardner noted, could cost the state some $672,000 a year in federal revenue and require complainants to have to file both local and federal actions, leaving businesses to have to defend against two cases.

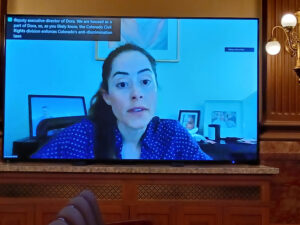

Aubrey Elenis, director of the Colorado Civil Rights Division, speaks via video in opposition to the POWR Act in early April.

But co-sponsoring Sen. Julie Gonzales, D-Denver, said she and Winter reached out to the EEOC and got a letter on April 18 saying that that change in definition would not jeopardize the work-share agreement the organization has with the state. Gonzales said during debate in the Senate on Wednesday that an official in the EEOC’s legislative affairs office said that the testimony was the result of a miscommunication.

The POWR Act is widely expected to pass the House before the May 8 end of the legislative session and make its way to the desk of Gov. Jared Polis. But with changes that business and local-government groups worked to bring about, it’s likely the focus of chambers of commerce over the final two weeks of this session will turn to trying to defeat other bills, such as House Bill 1294 and its efforts to study a ramping-up of air-quality permitting regulations.