A governor-appointed air-quality planning board will ask a state commission later this year to impose new regulations that eventually could limit emissions from gas-powered-vehicle traffic to warehouses, entertainment venues, airports and universities.

The Regional Air Quality Council plans by November to ask the Colorado Air Quality Control Commission to consider implementing the state’s first rules to limit “indirect sources” of emissions — venues and destinations that attract large amounts of traffic. While a pair of districts in California have similar rules, just in relation to warehouse traffic, no state has implemented such a plan before.

Even as members of the RAQC have been discussing the ideas for months, it’s not clear what the path forward would be. A Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment official told the RAQC board in March that his department, which oversees air-quality rules, isn’t comfortable running such a program yet, particularly until it determines the resources that would be needed to do so.

Still, Kyra Reumann-Moore, the RAQC’s air quality planner and analyst, said she hopes to get the council board’s endorsement for a final plan by October and then bring it to the AQCC in November as part of a larger air-quality blueprint. While many of the AQCC’s proposals, including the increase in fees and reporting around toxic air contaminants that it approved Friday, come from CDPHE staff, outside groups like the RAQC can bring proposals to it as well.

Why target indirect sources of emissions?

In the case of these indirect-source rules, the RAQC has worked closely with environmental groups Earthjustice, GreenLatinos and Western Resource Advocates to develop the proposal. While each proposal would start by requiring reporting from indirect sources on traffic to their facilities and then could evolve into recommended best practices, advocates argue the key to having the biggest impact will be requiring new steps for these sectors to cut greenhouse gases that their visitors are producing.

Coors Field is one of the venues that could be impacted by indirect-source rules.

“The RAQC emphasized its goal is to recommend a plan or strategy that would result in tangible emissions reductions,” said Jessica Zausmer, associate attorney for Earthjustice. “We certainly see that as an option to getting to a best-management-practices document but also ensuring those practices are regulatory, not optional.”

While each sector that could be targeted by the new rules has its own concerns, the overarching worry from business leaders is that they would be subject to costly new regulations whose impact on the Northern Front Range’s air quality remains unknown. State leaders are using a bevy of mandates to bring the area out of severe noncompliance with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ozone standards, but they can’t do something that would cause more economic harm than result in environmental good, skeptics said.

“What are we trying to accomplish here?” asked David Fridland, Denver International Airport environmental sustainability manager, at the March 25 RAQC board meeting. “Any increase in reporting burden or regulatory burden really needs to have a strong basis in ‘This will lead to some level of (emissions) reduction.’ And I’m not sure we’ve seen that yet.”

How the plan could work

One of the ideas that participants in the discussions have offered would require entities in each of the four sectors proposed to track vehicle trips to their facilities and, except for warehouses, to track transit trips there as well. Each also could be required to report on on-site electrification efforts and associated reductions within their footprint, and both the warehouses and entertainment venues also would have to track any reductions by the facility outside its footprint, some have suggested.

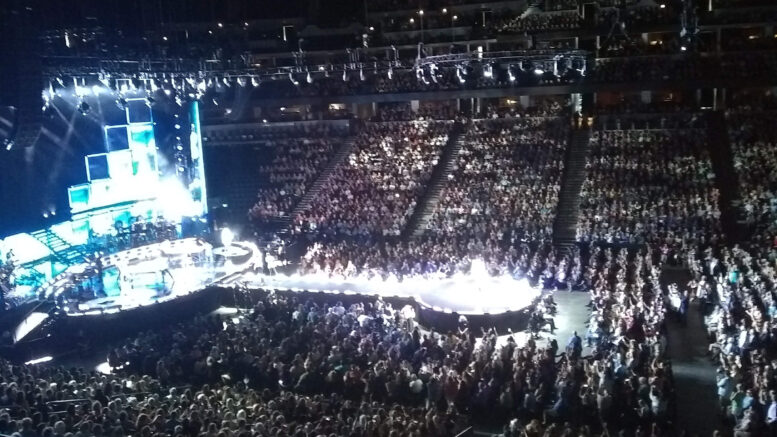

Concerts like those given by Taylor Swift attract a ton of vehicle traffic that a new emissions-reduction proposal hopes to address.

The tracking, Zausmer explained, ideally would happen in 2026 and 2027, after which the AQCC would be required to set either mandatory or voluntary emissions-reduction goals, like it’s done for sectors including oil and gas, manufacturing and commercial buildings. While the RAQC could help to collect and analyze data on each sector, it would have to be the AQCC that would impose compliance if any regulations were to be put into place.

“This idea of indirect-source emissions reductions is all about the reducing of trips to these facilities,” RAQC Executive Director Mike Silverstein said in March, noting that the sectors were chosen because of their high concentrations of vehicle traffic. “This is just one area that the RAQC has jumped into to say: ‘What else can we do to reduce vehicle emissions, as we have been directed to do?”

But even if state regulators change their mind and decide that this is an area where they would seek to regulate — likely with rules focused on the Front Range nonattainment area stretching from Douglas County to the Wyoming line — it won’t be easy.

Bus schedules, funding shortages create problems

Cutting vehicle traffic to entertainment venues like sports stadiums and concert halls likely would mean shifting patrons to transit, but transit agencies can’t easily set up service for specific events, Regional Transportation District bus operator Dan Merritt told the RAQC. RTD sets its schedule four months in advance and can’t shift on a dime, and its charter requires providing equitable service to all parts of the district, meaning it could run into problems creating specific routes to affluent areas like those where many venues are.

And even RAQC board member Mike Fronapfel acknowledged that other strategies will not fly with venue operators.

“I think it’s going to be very hard to say, ‘You should limit the people coming to your games,’” Fronapfel said at the Nov. 20 RAQC Control Strategy Committee meeting.

Universities and colleges like Colorado Mountain College in Edwards could be subject to new indirect-source rules.

DIA, meanwhile, is undertaking sustainability initiatives but doesn’t have a ton of funding available to track the numbers and destinations of its vehicle traffic or invest heavily in electric-vehicle chargers, principal airport transportation manager Lisa Nguyen said.

Fear that excessive emissions regulation will hurt business

And colleges face the prospect of implementing costly new programs through this plan while they are struggling to maintain existing funding during a budget shortfall, said Glenn Adams, University of Northern Colorado director of environmental health and safety. Also, he and others said, new regulations could be duplicative of transportation demand-management plans that most universities are implementing.

In the warehouse space, existing plans in California as well as this proposal seem to suggest that compliance looms with the installation of more electric-vehicle-charging stations, industry leaders said. But these are expensive technologies that many trucking companies that would frequent warehouse areas would struggle to afford, even if the plan, as suggested, would limit regulation to areas of 10,000 square feet or more, which represents about 41% of Front Range warehouses.

“I don’t want something to pass that’s largely an advertisement for the Utah Chamber of Commerce or the Wyoming Chamber of Commerce,” said Colorado Retail Council President Chris Howes, whose members operate numerous warehouses. “I can just see the pitch: ‘So many regulations that Colorado is no longer a safe place to do business.’”

The next step for the RAQC will be to develop estimates of potential emissions reductions from the menu of strategies and consider potential strategy elements and timelines, Reumann-Moore said.