Colorado legislators will consider a bill in 2024 that would require owners of short-term rental properties to pay the same property-tax rates as hotel operators, embroiling them in a debate over whether such a law would hurt or harm local workforces.

The Legislative Oversight Committee Concerning Tax Policy on Tuesday advanced on a partisan, Democrat-led vote a draft bill that would require residences that are rented on a short-term basis for at least 90 days a year to pay property taxes at the commercial rate. Were it to become law, the bill would take effect in 2026 and would boost taxation of those properties from 7.15%, as it is scheduled to be under existing law, to 29%, more than quadrupling their tax bills.

Supporters, including elected officials from many ski-town mountain communities, argue that the popularity and profitability of renting second homes on a short-term basis has left destination areas short of affordable housing and, thus, struggling with workforce shortages. It also has left local governments short of the funding they need to offer services to commercial properties, and officials like Summit County Commissioner Elisabeth Lawrence said they believe this law could push property owners to offer their space as long-term worker housing.

“Plain and simple, these are commercial buildings in residential neighborhoods,” Lawrence told the committee during a lengthy public hearing centered on the proposal on Tuesday, explaining some of her rationale for supporting the coming bill. “This is an income-producing investment. To me, that is a business.”

Major pushback from short-term rental owners

But while a string of 74 rental-property owners or management companies agreed they view their properties as investments — with some saying it will seed their retirements and others saying the money is needed to help them afford homes — they said it’s not fair to tax them like they are 100-room hotels. Particularly because the boost in property-tax bills could be larger than annual income that some make on their properties, many warned they would stop renting their homes for more than 90 days, which could lead to revenue declines for local businesses and local governments.

Numerous residents also warned that rather than move properties to long-term rentals, as local officials hope, they would take them off the market altogether, which would do nothing to address the lack of workforce housing several said they believe large employers should provide.

In fact, several witnesses on Tuesday questioned whether the bill was meant to help national and international hotel operators and the private-equity firms that could swoop in to purchase and resell high-dollar property that current residents can no longer afford to keep. That too could exacerbate the ongoing affordable-housing crisis by taking away valuable sources of secondary income from residents trying to afford the rising cost of living here, they said.

“This bill doesn’t compare apples to apples. We’re not wealthy corporations. This bill makes the rich richer and the poor poorer,” Denver real-estate investor Mike Brockway said. “You’re targeting the wrong people. We’re not hotels. We don’t own 100 units.”

Part of the larger housing debate

The debate over short-term rentals — one of several subjects studied this offseason by the tax-policy committee — comes as state leaders are seeking a way to lessen property-tax hikes that are slamming Coloradans as property values rose an average of 44% over the past year. Voters on Nov. 8 will decide whether to enact Proposition HH, a legislative initiative that would lessen the rise in property taxes in exchange for residents lifting the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights revenue cap significantly over the next 10 or more years.

Colorado state Sen. Chris Hansen discusses bill on the Senate floor during the 2023 session.

Sen. Chris Hansen, the Denver Democrat who will sponsor the bill, has been the driving force for several years behind the discussion of whether short-term rentals should be taxed as commercial property. He said Tuesday that the issue is one of tax fairness and equity as homeowners and national investors are generating significant revenue while facing a much lesser tax burden that the businesses around them.

The debate also comes as local governments, particularly in mountain towns, have begun imposing their own restrictions in recent years by capping the number of short-term rental licenses they will give, limiting the amount of time homes can be rented and imposing local fees on the properties. A group of 140 property owners are suing Summit County — the target of animus from many of the witnesses opposing the proposed bill on Tuesday — over its recently enacted law limiting vacation-rental properties in certain unincorporated areas to 35 bookings per year.

CJ Willey, corporate counsel at Evolve Vacation Rental in Denver, estimated that if a significant percentage of short-term-rental property owners limit booking to 90 days or take their homes off the market altogether, the state could lose some $500 million annually in tourism spending. The single-rental-property owners who operate 89% of such homes likely would rent only during the highest-margin times, such as major winter holidays, and their withdrawal of housing options during other times could deal a “death blow” to the mud-season economy, he said.

Partisan divide on short-term-rental taxation

Hansen and sponsoring Rep. Mike Weissman, D-Aurora, said they remain open to whether the threshold for conversion to commercial-property status should be 90 days or higher, though they rejected a proposed amendment from Rep. Lisa Frizell, R-Castle Rock, to set that threshold at 365 days of bookings each year. But they described the law as one that is necessary to generate more revenue for cash-strapped counties and that can open more housing options for the employees of the ski resorts, restaurants and other businesses in tourist destinations.

“Some businesses do not open because they do not have enough employees — because they can’t hire employees who live nearby,” Weissman argued. “At a very high level of abstraction, this is the law trying to catch up to the times.”

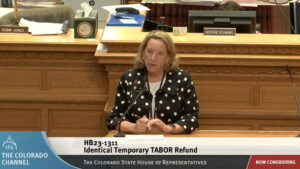

Colorado state Rep. Lisa Frizzel discusses a bill on TABOR refunds that is tied to a the Proposition HH ballot measure.

Sen. Larry Liston, R-Colorado Springs, argued, however, that the proposal is an example of how “the heavy hand of government is trying to tell you how to run your business” and cited Denver Realtor Bobby Reginelli, who said this is part of a greater erosion of private-property rights. And Frizell said she is concerned about unintended consequences ranging from a slowdown of business if property owners choose to just let their homes remain unoccupied to potential harm to real-estate markets if a lot of second-home owners feel forced to sell at the same time.

“It is not lost on me that the support for this particular bill only comes from government officials and counties, and that concerns me,” Frizell said. “We’ve been mandated by the governor to work to make Colorado more affordable, and I don’t really see how creating havoc in our tourism industry achieves that.”