As Colorado officials finalize long-awaited rules for a statewide recycling program, they are grappling with an issue that affects a small portion of packaging but that could impact a sector of businesses bigtime: Whether to count chemical recycling of plastic as an allowed form of recycling.

The debate over the somewhat-controversial method of breaking down for reuse the hardest-to-recycle plastics comes as a producer-responsibility organization gets ready to set fees by Oct. 31 on companies that create packaging for goods sold in Colorado. Those fees, to be assessed beginning in January, will fund a recycling program offered at no cost to households across the state by mid-2026 that will expand later to small businesses.

Circular Action Alliance, the non-profit in charge of the producer-responsibility organization, will assess different fees on different packaging materials, based upon the tonnage of materials in circulation and the recyclability of each material. The goal is not just to fund the statewide program but to boost Colorado’s anemic recycling rate — pegged as low as 16% of reusable materials by some studies — to 55% over the next decade.

As part of those goals, CAA leaders have established recycling targets for each content type. The recycling rate for glass packaging, for example, should rise from about 15% to about 35% by 2035 and for paper and metal packaging should jump from about 30% to about 45%, according to the proposed plan. But the most exponential jump is targeted for flexible plastic packaging — from about 1% now to 10%.

Some plastics hard to recycle

A worker feeds plastics into an advanced recycling reactor.

The trick is that those materials as well as some rigid plastics — from the thin plastic wrap used to keep vegetables fresh to film coverings to the harder plastic required for some medical-grade packaging — can’t be cut down the same way as mechanical recycling. While that method — which involves washing, grinding and reforming materials from paper to metal to easy-to-recycle plastics like bottles — works for some plastics, it’s useless with some flexible materials that clog up grinding gears.

As such, leaders in the plastics sector are developing a process of advanced recycling in which the material is melted to reduce it to its chemical building blocks and then reformed into plastic material. While the “mass balance with free allocation” process is still getting tested in numerous places, it holds an opportunity not only to reroute plastics that are now going into landfills but to reduce emissions from vehicles hauling new plastics if an end-market system grows in Colorado, said John Hewitt, senior vice president of the Consumer Brands Association.

But chemical recycling has some very vocal opponents, who argue through studies that the system is unproven, is far too expensive to be economically feasible and releases toxic waste and hazardous materials. After extensive debate, the advisory board for the producer responsibility program asked Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment Executive Director Jill Hunsaker Ryan to conduct a rulemaking on whether the method can be counted in the state as recycling.

Plastics groups pushing to allow chemical recycling

The final decision will be Hunsaker Ryan’s, though some plastics-sector leaders argue that the 2022 law creating the recycling program did not specifically ban chemical recycling, as it did for at least one other method, meaning she shouldn’t be able to ban it either. Without being able to use advanced recycling, proponents of the method argue, packaging producers facing higher fees because of the lack of their plastics’ recyclability either will jack the cost of those products or just stop making them, which could cost jobs.

The effort to permit chemical recycling through the program has the support not only of plastics groups but of some labor groups that also fear the loss of jobs from the action. That pits it against national organizations like Beyond Plastics that argue that argue that states should go as far as declaring a national moratorium on new chemical recycling plants — efforts gathering support from some local environmental groups as well.

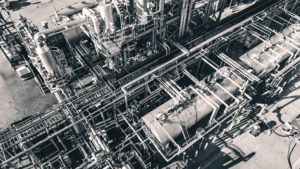

The Alterra Energy advanced recycling plant in Akron, Ohio

And because Colorado’s producer responsibility organization is the closest to going live out of the seven states that are developing similar programs, observers feel the state’s decision on this issue will have national reverberations on what other states will or won’t permit.

Advisory board questions efficacy of practice

“For the Colorado law to succeed, we believe this allowance is very, very significant,” said Ross Eisenberg, President of America’s Plastic Makers, the public-facing division of the American Chemistry Council. “Producers pay this fee to help develop the infrastructure to recycle their packaging products. But if you’ve taking in the money and you’re not recycling the materials … then the fee is essentially a tax.”

To be sure, the Aug. 14 letter that Elizabeth Chapman, chair of the producer responsibility program advisory board, sent to Hunsaker Ryan did not ask her to ban the process from counting as a method of recycling. But because there was a lack of consensus surrounding the method, Chapman included a statement of concern that the method may not provide the level of certainty and transparency that it can produce post-consumer recycled content that can be turned into new materials — or that the material isn’t turned into fuel, which is banned in the bill.

In an interview, Chapman insisted that the top obstacle to boosting plastic recycling is not potential disallowance of chemical recycling but human choice, as most easily recycled plastic is either tossed in trash now or is unclean and rejected by recycling-facility sorters. Plastic itself — and particularly the flexible plastic at issue here — represents a very small portion of the overall waste flow that the advisory board is trying to reroute to recycling facilities, and this one method won’t move the needle much, she said.

“Far beyond looking at plastics”

Tanks at the Alterra Energy advanced recycling plant in Akron, Ohio

But she felt it important enough to call out this issue because advanced recycling remains an unproven technology with high costs that has raised a lot of questions regarding its environmental impact and its impact on boosting recycling, she said. And even if Hunsaker Ryan can’t technically choose to ban the method from qualifying as recycling, state leaders could choose to increase the fees on this type of packaging to the point where it would be financially impractical — if they feel it poses dangers.

“I don’t see this as an urgent puzzle to solve,” Chapman said of allowing chemical recycling to count the same as mechanical recycling. “What we are concerned with is far beyond looking at plastics. We are trying to make recycling all materials economically and technically feasible in Colorado in a way that it isn’t now.”

Ultimately, the debate revolves not only around whether chemical recycling is safe but whether its allowance could create an end market for the material — essentially a loop where it is recycled in the state and then sold to companies that will use the recycled material as packaging. The only material with a full end market in Colorado right now is glass, and observers have cited the higher cost of having to ship recycled materials out of state as a reason why entrepreneurs have been slow to launch recycling facilities here.

Will advanced recycling create new end markets?

Beyond Plastics argued in a 2023 report, in which it cited the cases of numerous slow-to-produce or already-shuttered chemical-recycling plants in America, that there is no evidence that the practice can economically recycle mixed plastic waste. Thus, to the extent that it takes hold, it will replace rather than supplement mechanical recycling, meaning that it won’t contribute to any new end-market cycles.

The proposed plan from the Circular Action Alliance, though, notes if the new program doesn’t boost plastics recycling, that could leave a lack of supply of rigid plastic packaging, which could create challenges for small-scale producers to access sufficient quantities of some resins.

Eisenberg noted that some 45% of plastics going into landfills is from packaging and that roughly half of that total is the flexible plastics that need advanced recycling, meaning that only the allowance of new technology will create an end market and divert that waste.