If Colorado is going to seek to promote nuclear-energy projects in the state, it won’t do so by declaring the fission process to be clean energy.

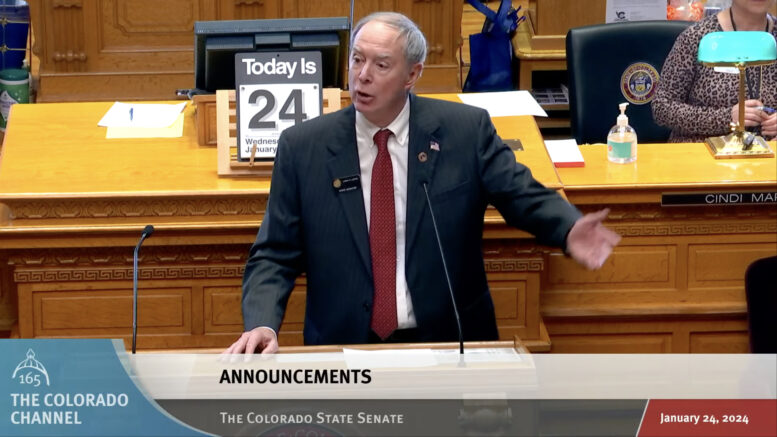

Democrats on a state Senate committee Wednesday killed a bill to promote nuclear energy by redefining it as clean, which would allow it to be used to meet statewide renewable-energy goals and qualify projects for clean-energy project financing. It was the second straight year such a bill died in the Senate Transportation & Energy Committee, signaling that the majority party, while backing reduction in fossil-fuel use, wants to concentrate on solar, wind and geothermal even in the face of a federal nuclear push.

Sen. Larry Liston, R-Colorado Springs, and a group of nearly three-dozen supporters argued that the energy is more reliable than solar and wind in inclement weather and that it will be needed to meet the state’s goals for a zero-emissions power grid by 2040. The proposal, he argued, would have brought Colorado in line with federal Inflation Reduction Act standards at a time when the federal government is offering tax breaks for nuclear research and development and pushing it as a clean energy.

“Nuclear stands for hope. It builds communities,” said Grace Stanke, a recent former Miss America who’s dedicated herself to nuclear promotion and pointed out that Colorado School of Mines has a nuclear-engineering programs whose graduates can’t work in-state. “The science is there. We just need to give it the green light to let this happen.”

Grace Stanke, a former Miss America who has promoted nuclear energy, is recognized Wednesday in the Colorado Senate.

Dual reasons for opposition

But environmental groups pushed back against the proposal on two grounds. First, many noted that the production of such energy requires mining of uranium, which is not clean. And most then added that it is not cost-efficient.

Paul Sherman, climate campaign manager for Conservation Colorado, cited the World Nuclear Energy Status Report in noting that solar costs dropped 90% between 2009 and 2020 and wind costs dropped 70% while nuclear costs rose 33%. Several testifiers noted that escalating costs have derailed a host of touted nuclear projects in recent years and said that Colorado should not use its policy levers to promote the sector.

“Investing in nuclear energy worsens the climate crisis because it redirects money that could be used for more proven and more cost-efficient energy sources,” Sherman said.

The debate occurred less than a month after a citizens’ committee in Pueblo issued a report saying that only construction of a small modular reactor could fill the economic hole that will be created when Xcel Energy shuts down its Comanche 3 coal-fired plant in 2031. In a twist, however, the co-chair of that committee told The Sum & Substance that reclassification of nuclear energy as clean energy could hurt the area because a 2021 law changed how clean-energy equipment is assessed reduced the near-term property-tax revenue that local governments can get from it.

Future of discussions around nuclear energy?

This is a rendering of the Natrium demonstration plant — a nuclear reactor project being developed in Kemmerer, Wyoming near a retiring coal facility with technology from Washington-based TerraPower.

To remedy that issue, Liston tacked an amendment onto SB 39 Wednesday that would have allowed local governments to assess nuclear-energy equipment based on the cost of its construction rather than the income it generates — a change that would boost upfront revenue for communities like Pueblo that could welcome the equipment. That addition earned the bill the support of Democratic Sen. Nick Hinrichsen of Pueblo, who said that he appreciated that the measure would not greenlight these type of energy projects so much as it “allows the conversations to begin in earnest” about them.

However, the other four Democrats on the committee opposed SB 39, offering concerns about spent nuclear waste and about the cost of producing such power. Sen. Faith Winter, D-Broomfield, said that as currently available renewable resources will allow Colorado electrical grids to be 98.5% carbon-free by 2040, the cost to tack on nuclear to get to 100% now seems too great.

“This does not open or shut the door on nuclear,” said Winter, chairwoman of the committee. “I’m not against trying to figure out how nuclear works in Colorado. But it’s more than just changing a word to ‘clean.’”