A bill that would make Colorado the first state in the nation to give local governments a first right of refusal on many apartment complexes that go up for sale received its long-delayed approval from the Senate late Saturday following a sometimes-rancorous debate.

House Bill 1190 and its controversial policy still must receive concurrence from the House on the significant changes it’s undergone from its original form, and it must get a signature from Gov. Jared Polis, who’s focused his housing-reform lens so far on building more housing units. But after being delayed on the Senate calendar since April 4, a bill that many legislative observers felt had reached an insurmountable wall moved forward, with another round of amendments, to what is expected to be official final approval from the body on the next-to-last day of the 2023 session on Sunday.

Republicans did not allow it to pass easily, holding it up for nearly five hours in debate in which GOP Sens. Bob Gardner of Colorado Springs and Barbara Kirkmeyer of Brighton picked apart every detail of legislation they said will have a chilling effect on multifamily housing investment. By the time co-sponsoring Sen. Faith Winter, D-Westminster, allowed a final amendment to tone down its provisions onto HB 1190, she said the changes may make it hard for governments to use the new law — but the amendments seemed to ease the fears of skeptical Democrats.

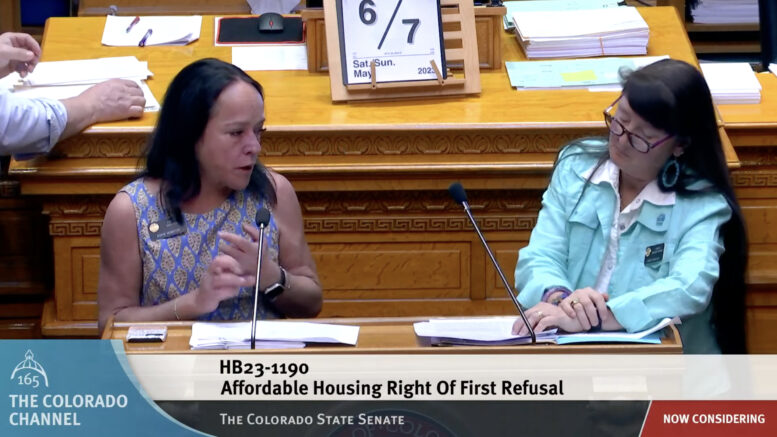

Colorado state Sen. Faith Winter speaks on the right-of-first-refusal bill in the Senate Saturday.

Details of the right-of-first-refusal bill

As the measure stands now, owners of certain apartment buildings that have reached a tentative agreement to sell them must allow their city or county governments the opportunity to step in and purchase them for the same price that they’ve been offered by a private party. Supporters have said that this will give cities and counties the ability to use limited resources to keep affordable housing from being sold to out-of-state investors who improve the buildings and raise the rents, shrinking the already-limited amount of local below-market housing stock.

HB 1190 would grant a right of first refusal on any multifamily housing property of at least five units in rural/resort areas or 15 units in urban counties — up from three and five in the original version of the bill — that is at least 30 years old, a condition added in a Senate committee. It would give those governments seven days to assert their right, 21 more days to make an offer and 60 more days to close on the deal, with the middle number reduced Saturday from 30 days.

With developers and operators warning the policy will drive away potential investment at a time when the state desperately needs more units, Winter and co-sponsoring Sen. Sonya Jaquez Lewis, D-Boulder, added or allowed more compromise provisions onto the bill. Major new amendments more clearly define the offer price that governments must match and require governments to indemnify property owners for lost economic opportunity if they assert their right of first refusal but don’t buy the property.

One final Republican change

While Democrats rejected Republican amendments to limit the new right to complexes with 500 units or more and to limit that right to complexes built with public money, they accepted one last amendment from Senate Minority Leader Paul Lundeen, R-Monument. That provision would allow property owners whose asking price is rejected by governments to sell the complexes for as much as 10% less than that price without triggering a second opportunity for the city or county to match what is a “new offer.”

“Every amendment narrowing the properties … has made it harder and harder for our local government partners to utilize this bill,” Winter said, recalling complaints from county leaders that those earlier additions like the 30-year requirement curtailed potential property targets.

Colorado state Sen. Dylan Roberts adds an amendment Saturday to the right-of-first-refusal bill.

But the new round of amendments appeared to get the bill past some of the Democrats who had expressed concerns with it, as more moderate caucus members like Sen. Kevin Priola of Henderson and Dylan Roberts of Avon authored some of the changes. And after a month of being in limbo, the bill appears to be unstuck.

“This is such an important tool for local governments,” Winter said, having noted that a good number of apartment sales are done with cash in just a matter of days, giving local leaders no chance to place a matching offer before the transaction is complete. “Let’s give them a chance.”

How the right of first refusal could change the market

Opponents noted, however, that it’s not about the matching price so much as about the potential buyers that will look instead to properties in other states so that they aren’t forced to wait three months to complete a purchase that they may or may not be able to make. Market conditions and interest rates can change substantially in that time frame, and investors will prefer to put their money into both new and used contracts where governments can’t swoop in and cut off their deals, a trove of developers told legislators in committee hearings.

And even the amendments that have been added do not provide as much protection as they might seem, several Republicans said. Both Kirkmeyer and Gardner focused on caveats in the 7-day/21-day/60-day time limits that allow local governments to extend the final time frame unilaterally if they have trouble completing surveying or financing through no fault of their own.

“It takes a long time to get surveys done. It takes a long time to get your financing in place,” Kirkmeyer said, adding that her daughter recently took 75 days to get someone to come out and survey her property. “We’re trying to pass a bill that says the government has the right to your property before everybody else, so you can’t go sell your property.”

Colorado state Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer speaks against the right-of-first-refusal bill in the Senate on Saturday.

The other big housing bill

The preliminary approval of HB 1190 came one day before the Senate is scheduled to consider massive changes that the House reinserted into the land-use reform bill that is at the center of Polis’ affordable-housing package.

SB 213 originally proposed minimum density levels along key and transit-oriented corridors in urban-area cities in order to spur more multifamily-unit construction. Under much municipal opposition to this pre-emption of local law, however, the Senate pared the bill back to requiring statewide and local housing-needs assessments to be done and banning a handful of practices, such as cities’ limitation on the number of unrelated individuals that can share a property.

But, feeling they’d missed an opportunity for bold action amid a housing crisis, the House sponsors of the bill reinserted most of the extricated provisions, including key-corridor density and the ability of most property owners to build accessory dwelling units on their land by right. And after several tumultuous debates, the House passed the newly rewritten measure Friday, leaving the Senate to decide today whether to agree to it, go to a conference committee to work out differences or stand pat on the much more moderate version it passed.