The Colorado Senate on Wednesday approved of a massive change in how injured employees can choose the doctors who will provide their workers’ compensation care, setting up an expected push for a veto from business and local-government leaders.

House Bill 1300, from Democratic Rep. Jenny Willford of Northglenn, would nix the ability of employers to provide injured workers with a choice of four potential doctors and instead let workers pick any Level I or Level II state-accredited workers-compensation provider. There are about 1,200 such doctors listed on the Division of Workers’ Compensation website, though the bill requires employees choose one within 70 miles of their home or office.

Supporters, including labor unions and advocates for injured workers, said the issue is in part an ideological one in which they seek to abolish long-standing law that lets employers largely guide their care, which can lead to a lack of trust with medical professionals. But Erin Montgomery — president-elect of the Workers’ Compensation Education Association, a group of attorneys that guided drafting of the bill — said her group deals with “thousands of employees” at any time who have issues with their care.

“Elsewhere in America, we get to choose our own doctor,” Montgomery told the Senate Business, Labor and Technology Committee on Thursday. “So, we think this is really a human choice that we should be able to choose someone to treat us with intimate medical care that is consistent with our beliefs, our personal priorities, our gender or any other category that is meaningful to the patient.”

Why employers opposed massive growth of workers’ compensation options

But that expansion in choice will bring with it far more costs than benefits, argued opponents that included local governments, industry associations, chambers of commerce and even the state workers’ compensation division.

Allowing employers to give workers a choice of a few vetted doctors can speed the beginning of care and ensure the worker gets proper treatment as soon as possible without having to sift through more than 1,000 options, opponents said. Unnecessary delays can hamper recoveries and cost employers in terms of increased medical bills, longer worker absences and potential increases in pay to temporary workers.

Employers also will lose a 2.5% credit on their insurance premiums that the state requires workers’ comp carriers to give them if they have a designated medical provider — a designation that the bill effectively bans. Jeff Cummings, president of Duffy Crane & Hauling, estimated he will lose $20,000 annually without this credit and surmised that with more than $1.1 billion in workers’ compensation premiums paid in Colorado, the net loss to employers could reach $25 million.

But the biggest concern, many said, lies with an extended timeline that workers can have to change doctors.

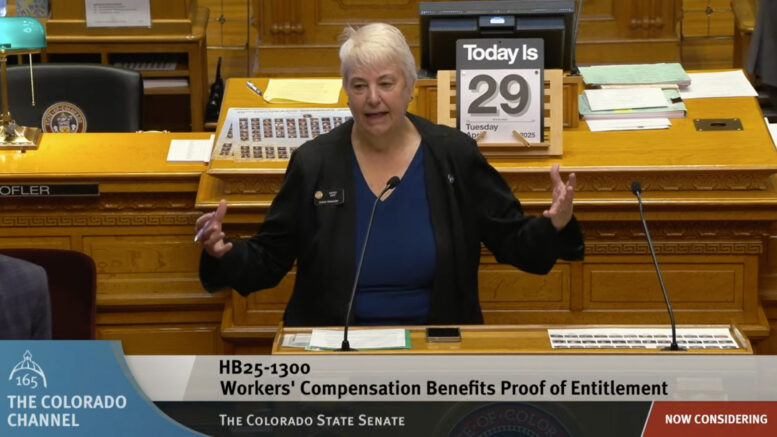

Colorado state Rep. Jenny Willford explains her workers’ compensation bill to the House earlier this month.

Will doctor-shopping become more common?

Both current and proposed law gives them seven days from the onset of the injury to choose a doctor for treatment and lets employers pick that caregiver if employees fail to do so. Current law allows them one change of doctor within the first 90 days of their injuries, and HB 1300 would expand that to 120 days if workers pick the provider initially.

However, if the employer chose the provider, employees under the proposed law still could designate a physician any time until they reach maximum medical improvement. That concerns employers that workers wanting to avoid returning to the jobs — a small but still pricey minority of workers, they admit — could doctor-shop for a provider who will lengthen their treatment.

Sen. Larry Liston, R-Colorado Springs, said he spoke to the risk manager of his home city, who estimated the impact of these changes would be to raise a $9.8 million annual workers’ compensation budget to $13 million. Paul Tauriello, director of the Colorado Division of Workers’ Compensation, cited a National Council on Compensation Insurance study saying that more workers going outside of network for care would boosts costs due to utilization of more expensive physicians.

And opponents across the board question why the bill is needed. Pinnacol Assurance, the largest workers’ compensation insurer in Colorado, noted that of its 35,000 claims last year, just 165 workers — less than 0.5% — were so unhappy with their provider that they requested a change.

Colorado state Sen. Larry Liston speaks against HB 1300 on Tuesday.

“While I know that we want to get help as soon as possible, the current system does work,” Liston told the Senate during debate on Tuesday. “All (HB) 1300 would do is delay their treatment, make it less efficient and make it more costly.”

Veto fight pending on workers’ compensation bill

Proponents did produce about a dozen patients who testified to the House and Senate committee about poor treatment they received from employer-recommended providers, which left them with permanent disabilities. Democratic Sen. Nick Hinrichsen of Pueblo said that while he’s spoken with officials from his city about their cost concerns, he’s also spoken with unions representing local workers who want the freedom of choice.

Spurred on by sponsoring Sen. Cathy Kipp, D-Fort Collins, Democrats in the Senate pushed the bill Wednesday to a 22-13 passage, with only Democratic Sen. Marc Snyder of Manitou Springs joining all the chamber’s Republicans in opposing HB 1300. That followed suit, as just three Democrats voted against it when the bill passed the House earlier this month.

HB 1300 returns now to the House for likely concurrence with Senate amendments.

But with the bill all but assured of landing on Gov. Jared Polis’ desk, opponents already are preparing their case for Polis to veto HB 1300, particularly as officials within the Colorado Department of Labor & Employment have come out in opposition to it. The request could pit the Democratic governor against labor unions even while he’s trying to negotiate a consensus solution to their bill to overhaul the Colorado Labor Peace Act and has said he does not want to sign the bill without a deal.

HB 1300 has changed very little during the process, taking on only a few amendments. A change in the House encourages employers to continue to provide workers with a list of recommended but non-binding providers, and a Senate change clarified that timeframes around doctor choices and changes are measured in calendar days. not business days.