Pinnacol Assurance has lost 10,000 of its 60,000 customers over the past decade because of changing workplace dynamics and must become a fully privatized firm to avoid raising premiums and cutting back services, its leaders told a legislative committee Wednesday.

The comments from the state’s largest workers’ compensation insurer — and its insurer of last resort — were the most extensive it’s offered during the months-long debate over Gov. Jared Polis’ conversion proposal, which could net the state some $500 million. Pinnacol President/CEO John O’Donnell and CFO Kathy Kranz told the Joint Budget Committee that they were “carefully considering” Polis’ proposal but did not detail any other scenarios in which the company could maintain long-term fiscal sustainability.

Pinnacol, while operating like a private mutual insurance company, is a state-chartered entity that has its board members appointed by the governor and gets considerable tax breaks as the workers’ compensation insurer of last resort. That means it must offer policies to companies with high risk and/or poor safety records that fully privatized insurers will not take on as customers.

While that arrangement — along with internal changes over the past two decades that have left Pinnacol with low claim-denial rates and high customer-satisfaction scores — have given the company financial success, its business model now is in jeopardy.

State law costing Pinnacol business

The pandemic-driven increase in remote work means that for the first time, most Colorado employers now have workers who live in other states, O’Donnell told the JBC. But because Pinnacol’s charter does not allow it to cover residents outside Colorado, it can only do so if it enters partnerships with insurers in other states that boost premium costs by 20%. And 95% of Colorado companies with employees in other states choose to do business with workers’ compensation provider other than Pinnacol to avoid the complexity and cost of those arrangements, O’Donnell said.

John O’Donnell is president and CEO of Pinnacol Assurance.

That’s led Pinnacol’s market share to drop from roughly 60% to 50%, and trends are likely to continue sending that share downward, said Mark Ferrandino, the director of the governor’s Office of State Policy and Budgeting who advocates for conversion. If Pinnacol continues to lose the business of larger employers, its risk pool will shrink and be dominated more by high-risk companies seeking policies of last resort, which will cause premiums that have been decreasing for all companies for years to rise again, O’Donnell said.

“Pinnacol is indeed at a crossroads,” said O’Donnell, who spoke for the first time to the six JBC members responsible for creating a balanced budget, which would include an infusion of $100 million next year from Pinnacol conversion under Polis’ proposal. “By staying status quo, we actually are on a path to increase premiums, (offer) less services in the future — and it’s just not a good place.”

What Pinnacol conversion could mean to budget

If legislators were to convert Pinnacol — a process that would require a separate bill later in this session — the insurer would have to pay the state a fee that Ferrandino estimated Wednesday as between $300 million and $500 million. OSPB currently is gathering bids from companies to evaluate the proper price, and he said he expects to award a contract on that project next week and have a firmer price for the JBC by the first week of March.

But Pinnacol also would have to pay to disaffiliate from the Public Employees’ Retirement Association, as its more than 650 employees are part of the public retirement system and PERA must still be able to cover its members’ benefits even with the assets from Pinnacol. Depending on the discount rate that Pinnacol will receive — a rate related to how quickly it repays its obligations — the disaffiliation cost will range between $183.5 million and $316.8 million, PERA CEO Andrew Roth told the JBC.

While both fees will land in PERA coffers, Polis plans to use the money not associated with disaffiliation to balance the budget by reducing the annual payment that the general fund sends to PERA to try to bring it to actuarial solvency by 2048. While Pinnacol would pay an agreed-upon amount to the state in one lump sum, legislators could break that amount up over several years to reduce general-fund payments to PERA by $80 million to $100 million annually over that period and be able to free up budget space.

Gov. Jared Polis (right) confers with Mark Ferrandino, director of the governor’s Office of State Planning and Budgeting, during a break in the JBC hearing on his budget proposal in November.

Legislators question Polis proposal

O’Donnell said Pinnacol would move forward with conversion only if it could maintain adequate capital and reserves to fulfill its obligations to workers and employers, and Kranz said that would mean keeping the fees down to no more than a combined $500 million. Pinnacol’s current reserve liability for injured-worker payments is about $1.3 billion, according to information it provided the JBC.

But even if Pinnacol and the governor agree on a conversion and disaffiliation price, the plan still must win the support of legislators — particularly those on the JBC. And Wednesday’s hearing showed that will be no slam dunk.

Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer, R-Brighton, asked if it would be easier if the Legislature just changed Pinnacol’s charter and allowed it to sell policies outside of the state. O’Donnell replied that while that would help, Pinnacol still would be unable to sell policies in 24 other states, all of which prohibit insurers that are an arm of another state’s government from operating within their boundaries.

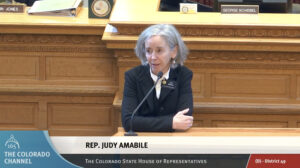

Rep. Judy Amabile, a Boulder Democrat and former business owner, asked if the company should be more focused on expanding the lines of policy it sells, as many companies try to bundle workers’ comp policies with other types of insurance. O’Donnell replied that even if the Legislature were to pass a low to allow that, it’s not an immediate expansion plan for Pinnacol because while that would help eventually, just being able to sell in other states is now “table stakes” for being a viable insurer in his sector.

Colorado state Sen. Judy Amabile speaks on the House floor during the 2023 legislative session in which she served in that chamber.

Debate will evolve in coming months

And Amabile and Rep. Emily Sirota, a Denver Democrat concerned about the impact privatization could have on injured-worker care, questioned whether Pinnacol conversion, if it’s such a good idea, shouldn’t be considered separately from the budget debate. Polis and Ferrandino have said, however, that with legislators needing to close a roughly $650 million gap in next year’s budget proposal, there are very few pots they can tap for revenue or cuts to offset the $100 million that Pinnacol conversion can offer immediately.

Sirota also offered skepticism that Pinnacol is in such bad shape, noting it’s been decreasing premiums and offering dividends to shareholder members for the past 10 years. Kranz explained that rate cuts have been required to keep up with a surge of new competitors but said they won’t be sustainable if Pinnacol continues to bleed interstate customers because of its statutory limitations.

Thus, Pinnacol leaders must walk a tightrope the next few months of convincing legislators that conversion is necessary to allow a company that is vital to the state’s workers’ compensation ecosystem to remain sustainable, even as its future viability is now waning. And in a session that won’t be lacking for major issues, this is an enormous one that could fly below the radar.