Waymo is operating driverless taxis in a handful of U.S. cities. Joby Aviation is testing air taxis that it intends eventually to fly without pilots. And Colorado officials are looking on with reactions that run the gamut from excitement to deep concern.

The age of autonomous vehicles, once envisioned only in futuristic cartoons like “The Jetsons,” has arrived. These new vehicles are taking to the roads and to the air in states surrounding Colorado, and a handful of limited-use and -distance cars and trucks already in operation here. But every advance brings more questions about whether Colorado has regulations in place to ensure safety from this emerging sector — without quashing innovation before it has a chance to take hold.

Legislators overwhelmingly passed a bill earlier this year that would have required drivers to be inside of commercial autonomous vehicles like semi-trucks, only to see it get vetoed by Gov. Jared Polis over his concerns it would imperil both safety and a nascent industry. The author of that bill, Democratic Rep. Sheila Lieder of Jefferson County, said she has continued to hold conversations with industry and labor leaders about the idea but has not decided yet whether to bring back her bill in the 2026 session.

Colorado state Rep. Sheila Lieder speak on the House floor during the 2023 legislative session.

As those talks roll on to an uncertain conclusion, however, pioneers in the sector are watching to see if Colorado is going to roll out the red carpet or hoist a similarly colored stop sign as they determine where they want to test their products. Waymo, manufacturer of autonomous taxis, announced in September that it plans to launch in Denver in the future, though the timeframe around when its cars would actually go into operations on the streets remains very uncertain.

“Guarantees you’re going to fail”

Skyler McKinley, a transportation policy official engaged with the Autonomous Vehicle Industry Association, said the discussion, which flew under the radar during the 2025 legislative session, is a very important one as the state tries to attract innovative industries. While safety-focused guardrails are reasonable for new technology, restrictions that go against the very purpose of a product — like requiring drivers to be in vehicles that are meant to operate without them — could act as a “Keep out” sign for companies thinking about growing here, he said.

“These companies don’t have to test in this market. They have the opportunity to go elsewhere where they are welcome,” McKinley, also the regional public affairs director for AAA — The Auto Club, said. “I would say that baking this into statute almost guarantees you’re going to fail when it comes to this level of innovation.”

Supporters of the bill disagree, saying that any restrictions would be focused largely on keeping fellow highway drivers safe, with some intent on protecting jobs as well, and that such a push would not derail innovation. This disagreement on the basic impacts of such a proposal demonstrates the gulf in how different actors view its importance.

“I’m keenly aware that this technology is amongst us. I’m not anti-technology. And I’m not a luddite burying my head in the sand,” said Sen. Larry Liston, a Colorado Springs Republican who cosponsored the vetoed House Bill 1122. “I just thought it was a reasonable idea. There needs to be some guidelines on where these are used, especially in big semi-trucks.”

State officials support autonomous vehicles

Legislators first thought about the coming technology in 2017, when they passed a law to establish the Autonomous Mobility Task Force, a group of state transportation and public-safety officials who must approve any AV that seeks to test in Colorado. The group has given the OK to several smaller vehicles now operating, including driverless shuttles that transport people to the 61st and Pena Station RTD stop and Colorado Department of Transportation autonomous truck-mounted attenuator vehicles that travel behind work crews to protect them.

A Colorado Department of Transportation graphic explains how the agency uses autonomous vehicles to keep work crews safe on highways.

CDOT leaders are bullish on autonomous vehicles, pointing during an Oct. 21 Transportation Legislation Review Committee hearing to reports that AVs tested elsewhere have led to a decrease in serious injury accidents and crashes with pedestrians. Kay Kelly, director of the Office of Innovative Mobility, argued that getting AVs onto roadways can not only improve safety but help immobile populations, such as the elderly and disabled, to regain transportation independence if they can move about without driving.

“An AV doesn’t get road rage. It doesn’t operate under the influence of drugs and alcohol,” Kelly said. “We can ‘What if?’ a lot on this topic. But I will say that, thus far, the data on AV deployments is very promising.”

But Lieder, Liston and other sponsors of HB 1122 persuaded a lot of legislators — 55 of the 65 representatives supported the bill in the House and 27 of 35 members of the Senate — that allowing driverless autonomous commercial vehicles, specifically those weighing more than 26,100 pounds, was a step too far. The bill would have prohibited the use of an automated driving system in those vehicles, essentially usurping the ability of the existing task force to decide what is safe.

A debate that parallels tech regulation

Despite the bipartisan support for the measure, Polis, who has shown he is loath to put many regulations on disruptive industries like technology in which the state wants to grow jobs, vetoed HB 1122. His veto letter sent the message that he feels autonomous vehicles can improve safety — and that he fears that overregulating the technology could preclude companies from using it in a range of vehicles beyond commercial trucks in Colorado.

“Since no other state has such a mandate, HB 25-1122 would effectively create a first-in-the-nation prohibition on autonomous commercial vehicle testing and operations,” the Democratic governor wrote.

The debate on regulating AVs comes as many legislators are trying to put guardrails around larger technology companies in the form of regulation of artificial intelligence and in proposed requirements for social-media companies to block criminal activity on sites. But neither Lieder nor Liston said they felt this issue was linked directly to the discussions about curbing the power of Big Tech because of its dimensions involving roadway safety and other unique issues.

The debate around autonomous vehicles, however, does have a direct link to labor issues, which have been particularly contentious over the past year at the Capitol. Polis in May vetoed a labor-priority bill that would have made it easier for workforces to unionize and take union negotiating fees directly out of each employee’s paycheck.

Autonomous trucks and labor concerns

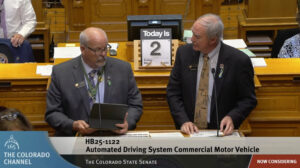

Colorado state Sens. Tom Sullivan and Larry Liston explain their bill on regulating autonomous commercial vehicles to the Senate in April 2025.

Liston said in an interview that it was the International Brotherhood of Teamsters who had approached him and cosponsoring Sen. Tom Sullivan, D-Centennial, about running the bill in their chamber. And Carl Smith — the state legislative director for the SMART Transportation Division, a labor union representing railroad crews, testified that protection of jobs in his industry was a motivating factor for his support of HB 1122.

“Since the trucking industry is the number one competitor of the railroad industry … if the trucking industry were allowed to have autonomous trucks, it would give an unfair advantage to it,” Smith told the Senate Transportation & Energy Committee on April 28.

Lieder, one of the biggest union supporters in the Legislature, said she sees the issue as being about both safety and labor. Elected officials absolutely should consider how autonomous technology can impact good-paying jobs, she said. But they also should look at how some companies in the sector, like PACCAR, have made decisions this year to place humans in the cabs of their test trucks, and they should ensure that Colorado is requiring the same whenever untested autonomous commercial vehicles come to state roads.

For now, Lieder said she is focused on “continuing the conversation” and will decide later if she wants to bring back a bill similar to the one that Polis vetoed. But both she and Liston said the questions surrounding whether large autonomous vehicles should be traveling on public highways without a human being in the cab to override the computer system won’t go away as long as more companies keep trying to develop the technology.

“It initiated a critical discussion,” Lieder said of the vetoed bill. “It’s about the delicate balance between safety and innovation. I just want to keep that going.”