As Colorado elected officials dive into a wide range of topics and controversies once the 2024 legislative session kicks off this morning, the need to find solutions to the state’s housing affordability crisis will have a role in almost every one of them.

Following the failure of Gov. Jared Polis’ wide-ranging 2023 land-use-reform bill that sought to spur multifamily construction, legislators again will try to boost development along transit corridors and in bedroom communities with the help of more local housing assessments. But this year, rather than debate the subject in one omnibus bill that by its nature carries a higher chance of failure, they will get to attack the topic in multiple bite-sized pieces, sometimes with competing bills seeking the same aims through different methods.

The topic is important to business leaders in many ways. Employers need more workforce housing to attract workers, who are increasingly shunning Colorado for more affordable destinations. Developers say they need changes in law to construct that housing. Some property owners want to have greater use by rights for their land.

But when municipal leaders erupted over Polis’ attempts to supersede local planning and zoning rules in Senate Bill 23-213 and the governor failed to include any construction-defects reform in his effort, many business leaders decided to stay out of the fight. That bill died at the end of the session, leading to eight months of conversations about what could find consensus support.

The new housing efforts

What’s coming is a flurry of bills that will mix a significant number of carrots with several sticks as well, explained Rep. Steven Woodrow, the Denver Democrat who sponsored SB 213 and will run the successor bill that is likely to attract the most significant debate. And at times they will be pitted against bills that either are all carrot or that step outside of the box of government and try to create solutions from market-based perspectives, like construction-defects reform.

“None of the policies are an overnight fix. What we have to do is increase supply. Even progressive Steven Woodrow recognizes this,” the legislator said, nodding to reports that have cited Colorado as being 120,000 housing units short of what it needs. “And when you want to build this stuff, you want to make it feasible. And you have to incentivize developers to come in and build this stuff where the market now tells them it’s not feasible.”

Colorado state Reps. Steven Woodrow and Iman Jodeh explain their land-use reform bill to the House during the 2023 legislative session.

To Polis, Woodrow and Democratic Rep. Iman Jodeh of Aurora, who will sponsor the main bill with Woodrow, the best way to do that is to require that cities allow for increased density in transit-oriented communities that can attract workers without requiring them to own cars.

Details of the central housing bill

Under a bill that they will introduce, urban cities and counties would determine the amount of land within their boundaries within a quarter- or half-mile of rail or bus rapid transit corridors and then set higher density allowances on that or adjacent land. A draft version of the bill would apply the requirements to 31 counties and cities — counties of 100,000 people or more and cities within metro planning organizations that have at least 1,000 residents, an average per-capita household income of $55,000 and 75 acres of land in proximity to frequent transit lines.

Those jurisdictions would get a minimum density requirement — sponsors now are focused on 40 units per acre — and be required to change zoning requirements to allow that density of housing over a designated area. To reach such density, a city or county could increase building-height maximums in some areas, could allow for buildings up to triplexes or quad-plexes in areas zoned for single-family housing or could permit multifamily construction in commercial or light-industrial zones, among other things.

Woodrow said that Sen. Dylan Roberts, D-Avon, will run a separate bill offering financial aid to local governments to help them undertake housing needs assessments to determine the price point and type of housing they lack most — a carrot rather than a mandate. It likely won’t be the only bill of its type, as Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer, the Brighton Republican who led the minority party’s fight against the mandates in SB 213 last year, has talked of a similar idea.

A renewed effort to allow ADUs

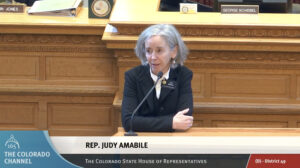

Colorado state Rep. Judy Amabile speaks on the House floor during the 2023 legislative session.

Meanwhile, Rep. Judy Amabile, D-Boulder, is poised to run a separate bill containing a key provision in SB 213 — a guarantee that property owners in districts zoned for single-family homes can build accessory dwelling units in their yards to house family members or others. SB 213 originally would have allowed also for homes anywhere from single units to six-plexes to be developed within single-family-zoned areas, but Amabile plans to limit her bill this year to ADUs, Woodrow said.

Colorado Municipal League Executive Director Kevin Bommer has said repeatedly that city leaders will continue to oppose any effort to usurp local control in the planning and zoning process, which could set up a fight over Amabile’s bill. But it definitely will set up a fight over Woodrow’s proposal because of its planned enforcement provision — a ban on covered jurisdictions receiving Highway User Trust Fund money to improve their roadways if they have not created new density allowances for these transit-oriented communities by December 2026.

“Local communities absolutely balked at that,” Woodrow said. “But we have to do something with teeth.”

Construction-defects reform

Meanwhile, Sen. Rachel Zenzinger, D-Arvada, is beginning to rally support from homebuilding and economic-development groups for a bill she plans to introduce quickly to bring about construction-defects reform. The measure would require defects lawsuits to be filed against specific contractors who created alleged problems rather than against the blanket construction team, and it would give those contractors a right to remedy the situation by working with residents to find an acceptable third-party firm to fix defects before any legal action can occur.

Zenzinger has said the bill is necessary because the dearth of condominiums being built — they represent just 3% of new housing starts in Colorado, according to the Common Sense Institute — is robbing younger workers of their ability to buy attainable homes and build equity. And groups like the Colorado Association of Home Builders have said that no matter how many obstacles Polis knocks down to putting up multifamily housing, developers won’t invest in building condos if they continue to be sued over their work at high rates.

Colorado state Sen. Rachel Zenzinger speaks about her coming construction-defects reform bill to the Colorado Chamber of Commerce’s Legal Reform & Litigation Alliance.

“You can’t have that conversation about affordable housing and ignore the fact that the most reasonable solution to affordable housing that’s out there isn’t being built,” Zenzinger told the Colorado Chamber of Commerce’s Legal Reform & Litigation Alliance in November.

Defects-reform pushback and other issues

Woodrow is not planning to support construction-defects reform, and he said that despite Zenzinger’s sponsorship, he believes the bill will find a lot of skepticism in his caucus.

“Tort reform didn’t make medical care any cheaper, did it?” he asked.

There will be other efforts too. Eve Lieberman, executive director of the Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade, told the Joint Budget Committee Monday that Polis is seeking to put $5 million toward helping communities convert office buildings into residences in urban areas.

In fact, housing will permeate just about every discussion at the Legislature this year. The question is: How many solutions can find enough consensus to become law?

The 120-day session begins at 10 a.m. today.