In 2023, as Colorado regulators developed the nation’s first emissions-reduction rules for manufacturers, business leaders argued compliance could come only with options that included a fund that businesses could pay into if they couldn’t hit reduction goals onsite.

Last week, however, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment ended its efforts to develop such a fund — a decision that officials said was influenced heavily by two factors.

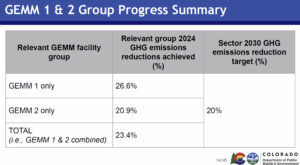

First, they noted, the reductions the sector is achieving are exceeding expectations — not just for where the industrial facilities were expected to be today but compared to where they were supposed to be in five years. While the 21 facilities regulated by the Greenhouse Gas Emissions & Energy Management for Manufacturers (GEMM) rules were required to cut emissions 20% by 2030 from 2015 levels, they achieved 23.4% reductions by 2024, said Megan McCarthy, CDPHE’s industrial manufacturing program manager.

A Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment chart shows the progress manufacturers have made in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Second, with the cuts coming so quickly, the lead organization that had sought creation of the State Climate Action Reserve Fund — the Colorado Chamber of Commerce — wrote to CDPHE and said it no longer believes the fund is needed for compliance. As such, emissions credit trading supervisor Cecelia White told the Colorado Air Quality Control Commission, officials won’t propose creating such a fund now, though they could discuss it in future years if it proves necessary.

“Reductions beyond their targets”

“The GEMM and midstream (oil-and-gas sector) entities are making reductions beyond their targets and what’s required,” McCarthy said. “The group has reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by 3.4% more than required six years before its deadline.”

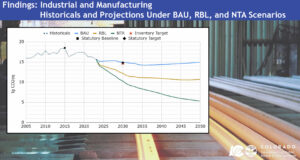

The large manufacturing sector was one of a handful of industries — including utilities, commercial buildings and oil and gas — given specific emissions-reduction mandates by legislators when they passed the Environmental Justice Act in 2021. That and subsequent laws require the state to reduce GHG emissions 26% by this year and 50% by 2030 versus 2005 levels and accelerates goals to getting to net-zero emissions by 2050 — targets the state projected to fall slightly short of in the near term, officials said.

However, the manufacturing sector (as well as the utilities and oil-and-gas sectors) has been a shining star and is on target to reduce emissions roughly 40% by 2030, McCarthy said. The reductions have been so great that few companies have sought to take advantage of a credit-trading program also authorized by the AQCC in 2023, as on-site improvements have pushed many into early compliance.

Goals for manufacturers

For GEMM 1 facilities — a quartet of steel and cement plants that face significant cost pressures from national and international competition — the goals focused on cutting emissions intensity rather than capping overall emissions. The 17 GEMM 2 facilities — which ranged from giant food-and-beverage plants to ethanol-production facilities to the Suncor USA refinery in Commerce City — each received individual mandates contributing to the sector-wide reduction goal.

Under the GEMM rules, the facilities are required first to make any feasible reductions to emissions on site, and those that don’t hit interim targets can purchase credits on the trading market. GEMM 2 companies, the only ones allowed to earn credits so far, must exceed 2030 goals to obtain and sell credits, which are considered incentive for them to make emission reductions more quickly.

At the end of 2024, GEMM 1 facilities had cut emissions 26.6% versus 2015 levels, and GEMM 2 facilities had reached 20.9% reductions, which combined for the 23.4% cut in emissions from the sector. Where the 21 facilities (a number that fell by one after the Carestream Health plant in Windsor closed) emitted 5.13 million metric tons of carbon-dioxide equivalent in 2015, they were emitting must 3.93 million metric tons in 2024.

Still, some industry representatives had pleaded with the AQCC as recently as May to move ahead with creating the reserve fund, arguing that it is a needed final option for hard-to-decarbonize facilities and for midstream operators who could be shut out of credit trading. The idea was to allow otherwise noncompliant firms to pay around $89 (equivalent to federal social cost of carbon) for each metric ton by which they exceeded their limits and to use the revenue for emissions-cutting projects in the industrial sector in disproportionately impacted communities.

A CDPHE chart shows the declines in emissions by manufacturers that have occurred and are expected to occur. The blue line represents what would be expected without state regulations, the yellow line is what is expected under current state rules and the green line represents what could occur with potential near-term opportunities such as an increase in carbon capture and sequestration projects.

Trading market proves eye-opening

But in June, CDPHE held its first credit auction and observed several important things.

First, the early emissions cuts resulted in the department releasing 175,184 credits onto the market — a total that represented roughly 82,000 credits more than the combined GEMM entities needed to achieve compliance by 2026. Second, just five companies bid on credits offered by just three companies at prices that generally fell below offer prices, showing there was not a huge demand for the credits, CDPHE officials explained.

Of the 16 GEMM 2 companies that have submitted plans — one of the 17 regulated businesses was given a stay of deadline — eight committed to make their needed reductions onsite by the end of this year and not use any credits, McCarthy explained. The other eight submitted reduction plans focused on 2030, and five said in them that they won’t need to use credits because they’ll achieve reductions with onsite measures.

Thus, officials have concluded, the credit market will be enough to allow paths to compliance for all regulated companies in the sectors.

How manufacturers are achieving reductions

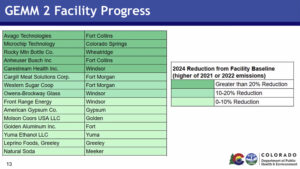

Several public commenters before last week’s AQCC meeting lauded CDPHE for its decision not to move ahead with creation of the reserve fund and specifically said they didn’t want to see Suncor buy its way out of its obligations. The refinery is one of three manufacturers expecting to purchase credits for compliance, along with the American Gypsum plant in Eagle County and the Natural Soda facility near Rangely, and it is responsible for half the emissions cuts the entire GEMM 2 group must make.

And while Suncor also has the largest gap between its required reductions and what it’s achieved so far, as commenters also noted, it has submitted plans to reduce the fourth-highest amount of emissions in the 2030 group — 31,156 metric tons of CO2 equivalent. Those reductions will come from energy-efficiency improvements, process changes and waste heat recovery, CDPHE officials said.

Overall, the GEMM 2 facilities are using a variety of methods to cut emissions onsite, CDPHE materials showed. Methane capture and destruction, carbon capture and sequestration, biogas recovery and use, energy-efficiency improvements and waste heat recovery all will play big roles in helping the sector achieve its goals.

Is there still a future for the reserve fund?

Even as CDPHE officials set aside the idea of creating a reserve fund as a last-ditch compliance measure for now, AQCC member Curtis Rueter cautioned against the department ending its work on this plan permanently. The fund always was seen as a last resort, and there may be a time when credits are harder to come by, particularly as compliance requirements for the midstream sector ramp up, and it could be needed to fund projects that will achieve costly emissions cuts, he said.

“My concern now is the trading market looks great and liquid. But if companies decide for whatever reason not to offer credits on the market, we’re still a small market with limited options,” Rueter said.

A Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment chart shows the magnitude of emissions cuts being made by certain manufacturing facilities

For now, though, the most controversial aspect of the GEMM plan — environmentalists so hated the idea of the reserve fund that they worked with Democrats to run an ultimately unsuccessful bill that would have overturned that part of the rules — is no more. And that’s in large part due to companies such as Avago Technologies, Microchip Technology, Cargill Meat Solutions, Western Sugar Cooperative and Molson Coors Beverage Co. going above and beyond state-set goals to reduce emissions.

“Most facilities are reducing emissions,” McCarthy told the AQCC during an earlier briefing in May. “We are starting to see early, deep reductions.”