Not content just to say they don’t want enforcement of proposed new labor laws funded with unemployment taxes, opponents of the idea convinced the Colorado Senate Monday to strike such funding from a bill and ban similar uses of Employment Support Fund money in the future.

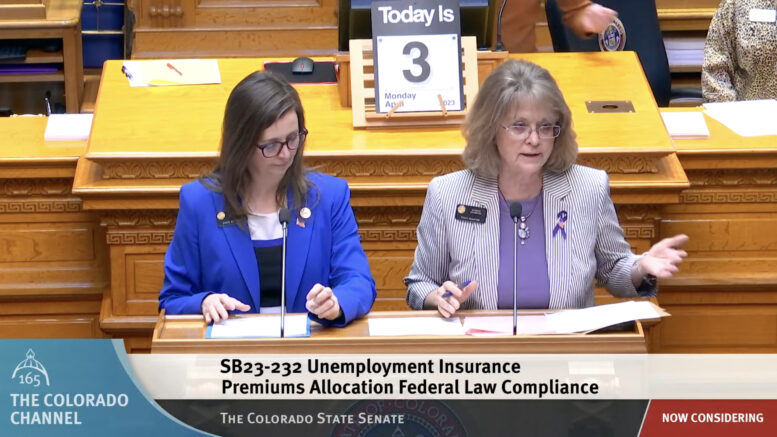

Senate Bill 232, sponsored by Democratic Sen. Rachel Zenzinger of Arvada and Republican Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer of Brighton, is an “orbital bill” to the state budget bill, meaning it’s meant to tweak aspects of state law in line with the $38.5 billion fiscal plan the Senate passed last week. Specifically, the proposal is meant to bring the 33-year-old ESF in line with federal law on the use of unemployment taxes and cap the amount of money going into the fund moving forward.

The ESF takes a small portion of taxes paid by employers into the Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund that provides benefits to laid-off workers and deposits them in a special account that was set up to help with administration of the UITF and provide local workforce-training grants. A 2001 bill expanded uses of the ESF to include labor standards, labor relations and the Colorado works grievance procedure, though it rarely has been used for those things.

However, fiscal notes attached to a half-dozen bills this year sought to fund enforcement of new or updated laws with some $3 million in ESF funds, and SB 232 originally included a provision to fund three 2022 laws from the same spigot to the tune of almost $900,000. On March 22, Colorado Department of Labor and Employment Executive Director Joe Barela wrote a letter to legislators expressing his “extreme opposition” to the idea and suggesting he may seek vetoes from Gov. Jared Polis of any enforcement bill using ESF money.

Changes to SB 232

As a result, the Senate held SB 232 back from the package of budget bills it approved and sent to the House last week, wanting to make several significant fixes to the bill. And on Monday, the upper chamber of the Legislature overwhelmingly agreed to those changes, which could go a long way toward meeting Barela’s wish of requiring new labor-law enforcement bills to get their money from the limited pot still available in the $14.7 billion general fund.

First, the Senate, without opposition, approved an amendment from Kirkmeyer that stripped money from SB 232 for enforcement of the three laws passed last year. Those laws — extending the state’s wage-theft law to misclassified workers, permitting collective bargaining for some county employees and licensing supplemental health-care staffing agencies — now will have to get a combined $899,537 for enforcement in the next fiscal year from the general fund.

Colorado state Sen. Bob Gardner speaks Monday on the Senate floor about SB 232.

Senators then approved another amendment, this one from Republican Sen. Bob Gardner of Colorado Springs, that repeals, as of July 2025, the 2001 law that allows ESF money to go toward enforcement of labor laws. It appeared in a vote that the only officials opposed to the move were the three Senate members of the Joint Budget Committee — not because they did not support the move but because, as Zenzinger explained, they had not discussed the plan with the entire JBC, which agrees to support or oppose budget bills as a bloc.

With the votes, the body seemed to back Barela in a bipartisan way, despite comments from some JBC members and staffers several weeks ago that funding labor-law enforcement with ESF money might be a smart thing to do in a tight budget year.

“The ESF had become a piggy bank that was being used any number of inappropriate — in my opinion — uses,” Senate Minority Leader Paul Lundeen, R-Monument, said. “This amendment would limit that and bring it back in line.”

What it means for unemployment taxes

SB 232, which must receive a final vote from the Senate this week before moving onto the House for consideration, could have several impacts on businesses.

Sponsors of the amendments to SB 232 speak Monday on the Senate floor.

First, by capping the amount of money that can go into the UITF, it will ensure that a greater percentage of unemployment taxes go to the UITF, which remains actuarily insolvent after going broke in August 2020 under a crush of pandemic-related unemployment benefit claims. Until the UITF reserves reach a level of about $1 billion — a target that is not expected to be hit now until 2025 — employers must pay a solvency surcharge beginning next year, and diversion of less money into the ESF could speed that push toward solvency.

The ESF cap is proposed at $32.5 million for the fiscal year beginning on July 1, and it would adjust annually in the future based on changes in the average weekly earnings of Coloradans.

Second — and this was a big reason behind Barela’s opposition — it means that more money in the ESF can go toward workforce-training grants rather than be diverted to labor-law enforcement. Barela, who rose from the local ranks before Polis chose him to be a part of his cabinet, told The Sum & Substance last month that such training is vital at a time when many industries face a shortage of workers who have the skills to do needed jobs.

Finally, if the Legislature follows through on the spirit of SB 232 and on Barela’s request to bar new bills from funding enforcement via the ESF, it will make it harder for some or all those bills to find the money they need to pass into law. With one of the six bills seeking ESF money already dead (the Fair Workweek proposal to require advanced scheduling for restaurant and retail workers) and another viewed as more of a proper use of unemployment-tax funding (House Bill 1078, which would create a $35 weekly stipend for the children of benefits recipients), four bills could be affected:

- SB 105, which would add more requirements to the two-year-old Equal Pay for Equal Work Act and double the allowable backpay from three to six years;

- SB 98, which would increase the amount of information that gig-worker companies like Uber and Lyft must provide to drivers regarding their payments;

- SB 111, which would grant public-sector workers the right to engage in organizing activities and participate in the political process in off hours; and,

- SB 17, which would allow workers to use paid sick leave to deal with the death of family members or to care for children when their school closes temporarily.