Pollution-generating companies within Colorado communities that are poorer, more ethnically diverse and addled with environmental problems soon will have to undergo enhanced modeling and monitoring in an effort to clean up such disproportionately impacted communities.

Colorado Air Quality Control Commission members voted unanimously Thursday, following a two-day hearing, for new guidelines that were set in motion in 2021 when the Legislature passed the Environmental Justice Act. The rules require the state for the first time to consider and attempt to lessen the cumulative impacts experienced by communities rather than consider individually the pollution coming from each stationary source when those sources seek permits.

For businesses seeking permits, this means they will have to file new environmental-justice summaries, will be subject to greater requirements that could add to their operating expenses and could see an already lengthy permitting process extended more. For communities from north Denver to Commerce City to Pueblo, it offers more opportunities to participate in the permitting-consideration process and the possibility of a decrease in volatile organic compounds, nitrous oxide emissions and other hazardous air pollutants.

Two days of testimony

Commissioners sought to balance the need to clean up areas of high air pollution with the feasibility and reasonability of burdens they could place on oil-and-gas operations, refineries, dry cleaners, distribution centers and other industrial businesses. And it was clear from the testimony of environmental, municipal, business and oil/gas groups on Wednesday and Thursday that the approved rules are not ones that either side particularly loves.

Complaints from business groups led to deletion of a key provision of the rules — a section that would have boosted scrutiny when permit holders sought minor modifications of facilities, which can now be approved administratively without enhanced modeling requirements. Commissioners seemed concerned about what this could have added to an average permitting time that Chris Colclasure, a partner at Beatty & Wozniak and former deputy director of the Colorado Air Pollution Control Division, said soared to 554 days in 2022.

Yet, commissioners kept in the rules a provision protested by groups like the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce and American Petroleum Institute that will require companies in targeted communities to install reasonably available control technology (RACT) to reduce air pollutants. Now a requirement only in federally designated pollution nonattainment areas, the mandate will go statewide beginning next year.

“If the commission were to impose RACT, the analysis would lead to increased time and costs for businesses,” Colorado Chamber of Commerce President/CEO Loren Furman testified. “If the division changes the threshold of what is cost-effective, that certainly, we believe, increases the challenges for the division’s permit engineers and businesses to determine when RACT is appropriate. And any uncertainty in cost, as we have said time and time again, could lead to more permitting delays.”

Representatives from groups such as the Colorado Chamber of Commerce, Colorado Competitive Council and Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce speak together against proposed new regulations before the Colorado Air Quality Control Commission on Thursday.

Criticism from a variety of groups

Meanwhile, environmental organizations criticized the rules for doing the “bare minimum” to meet Environmental Justice Act requirements, failing to expand the range of air pollutants for which modeling is needed and limiting the size of fees needed to launch community monitoring.

Ian Coghill, senior attorney for the Rocky Mountain office of Earthjustice, said his analysis showed that only 98 new or modified permits issued in the past three years would have triggered new source-specific monitoring requirements under the new rules. And only eight sources emitted enough benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene or xylene — common pollutants grouped together as BTEX — in 2021 even to trigger enhanced modeling.

“The division processes thousands of permits every year,” Coghill said. “But the number of sources that would be impacted by these rules is so small that it really can’t justify these thresholds.”

Disproportionately impacted communities

Disproportionately impacted communities, according to the rules, are those where 40% of households are at or below 200% of federal poverty level, 40% of the population identifies as people of color, 50% of residents pay at least 30% of their monthly income toward housing or 20% speak limited English in households. Of the 3,522 census blocks in the state, 769 qualify as socioeconomically vulnerable and 707 are considered cumulatively impacted, meaning some 40% of the state’s population lives in areas that could be subject to the new rules, said Joel Minor, environmental justice program manager for the APCD.

However, the rules differentiate between socioeconomically vulnerable communities and cumulatively impacted communities using a tool, Colorado EnviroScreen, that combines socioeconomic factors with environmental factors like exposure to air pollution and proximity of mining or drilling to create an impact score. Being tagged as a cumulatively impacted community creates stricter regulations for companies, including requirements of monitors to be placed on smokestacks to measure pollutants rather than to be placed within communities to measure pollution exposure.

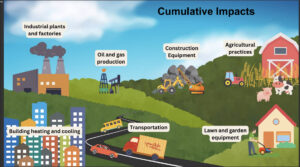

A graphic from the Colorado Air Pollution Control Division shows the multiple sources that can contribute to cumulative impacts in disproportionately impacted communities.

Companies subject to source-specific monitoring will be required to do RACT testing and add technology that is cost-effective and reasonably available. While natural-resources attorney Carlos Romo warned expansion of RACT could shut down some factories, Denver Department of Public Health and Environment air-quality supervisor Bill Obermann argued that RACT is a blanket analysis rather than a requirement for upgrades.

Questions about monitoring

Source-specific monitoring also could begin when pollutants such as benzene are discovered in community monitoring to be at 50% of levels that could impact public health, which APCD officials said is an effort to impose limitations before public health is affected. However, a group of municipal leaders complained that the monitoring does not consider some air toxins such as formaldehyde, and Broomfield Senior Environmental Epidemiologist Meagan Weisner said even that 50% mark is three times higher than the level of benzene emissions that has led to reports of headaches and other health conditions in her communities.

While increased regulation is contingent on Colorado EnviroScreen scores, officials from Garfield and Weld counties called the rating system a flawed one that doesn’t differentiate among large census blocks with multiple drilling sites and small census blocks with concentrated pollution. Annareli Morales, Weld County air-quality program environmental health specialist, noted the system shows some emission levels being 20 to 60 times higher in Pawnee National Grasslands and rural Garfield County than in Commerce City because of its methodology.

With the commission’s approval, the APCD will undertake a year-long period to put together both community and single-source-monitoring guidelines before putting monitoring requirements into place in mid-2024, air-quality planner Jessica Ferko said.

With staffers responsible for drawing up these specific guidelines, Adam DeVoe, attorney for the EVRAZ steel plant in Pueblo, warned that the AQCC rulemaking was just the tip of the iceberg. Most of the rules are yet to be set in stone, and that uncertainty creates concerns.

“The division is proposing a massive amount of guidance to implement the rule itself,” DeVoe said. “We are concerned about the lack of details … Their proposal is ‘Monitor everything, monitor all the time.’”