In many ways, the outcome of the 2023 legislative session for the health-care industry mirrored that of business in general: Employers fought off potentially stifling regulations, leading to heavily amended bills but little they could point to that may help them deliver better care.

In all, legislators introduced 116 bills dealing with health care this year, ranging from potentially seismic shifts in hospital reimbursement to tweaks in behavioral health care. Gov. Jared Polis continued his five-year-long crusade to try to save people money on health care, though he clashed at times with hospitals, health-insurance providers and pharmaceutical firms over the details of his plans.

The biggest impact of the session may have been to advance programs that Polis already has put into place as cornerstones of his health-care reform agenda. Legislators expanded the reach of the Prescription Drug Advisory Board (despite the two-year-old board not having considered price caps on any drugs yet), provided regulators more ability to limit the cost of Colorado Option insurance plans and killed a bill to study implementation of a single-payer health-insurance system that could have upended past reforms.

But to get to those ends, they first considered eliminating facility fees in a way that could have shut down hospital-owned clinics across the state, and they passed more new insurance mandates despite the Democratic governor’s insistence in 2020 that such mandates raise costs. And health systems and insurers, while avoided what they labeled as potentially “devastating impacts,” said they don’t feel like they’ll be able to provide any better care for their customers because of what Polis has signed and will sign into law.

“A lot of administrative requirements”

“At the end of the day, we mitigated a lot of damaging impacts. But what we were left with were a lot of administrative requirements on top of years of new regulations,” Colorado Hospital Association Vice President of Government Affairs Josh Ewing said in an interview. “And what we are still missing is: What is the best thing for patients?”

Colorado Hospital Association vice president Josh Ewing (foreground) answers questions Friday from Rep. Chris deGruy Kennedy (looking on) during a legislative committee hearing.

Leaders from the Colorado Division of Insurance and Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing, as well as several patient-advocacy groups, disagree with that sentiment. Over hundreds of hearings, they spoke of the need to boost transparency in the often-murky world of health-care billing and to do something to reduce the cost of pharmaceuticals in particular — and several said the passed health-care bills go a long way toward that goal.

“We are leaving no stone unturned in our ongoing plans to continue saving people money on health care and make sure Coloradans have the care and resources they need to thrive,” Polis said in a statement on May 10, when he signed a handful of key health-care bills.

Hospital facility fees

The bill that was most exemplary of the clash between the administration’s goals and the companies that operate health-care businesses was House Bill 1215. As introduced, it would have banned facility fees charged by hospital systems to patients getting care in off-site facilities – a practice that’s become increasingly common as more hospitals have purchased primary- and specialty-care practices over the past 20 years and moved services out of acute-care settings.

Supporters of the bill argued that patients were getting surprised and financially walloped by the fees, but hospital systems responded that the fees are their source of funding for equipment in facilities and for support personnel ranging from nurses to janitorial staff. Because the federal government bars hospitals from including those costs in standard billing, hospitals must break them out separately and would have to shut down clinics providing cancer treatment and behavioral-health care without such fees, officials said.

After 14 amendments across both chambers, the only facility fees that the final version of HB 1215 bans are those for preventive services, though the bill does allow hospitals to charge those patients’ insurers those fees if such fees are part of an agreed-upon contract. The heart of the bill now lies in a study that it requires HCPF to perform by Dec. 1 on the impacts of facility fees upon both patients and health-care providers.

Colorado state Reps. Andy Boesenecker and Emily Sirota explain their bill on hospital facility fees to the House in April.

“They sought to prohibit facility fees for no good reason other than ‘Gee, hospitals make too much money, and we didn’t have to pay facility fees when we went to our doctors’ offices back in the day,’” said longtime lobbyist Patrick Boyle, who represents several health-care clients. “The bigger picture is the session was really tough on hospitals and health plans.”

Health-care bills affected insurance

One of the main focuses for health insurers was HB 1224, which gives the insurance division more power to ensure that the Colorado Option standardized plans created in 2021 are reducing their rates annually. The division can limit what it considers as excessive profit and administrative expenses in determining rates, and it can develop a format so that such plans are easily identified on the Connect for Health Colorado exchange – a provision that irks insurers because it elevates these plans above other plans even when they are more expensive.

Sen. Jim Smallwood, R-Douglas County, complained during Senate debate that the Colorado Option plans are getting a leg up on the competition even though they were not the cheapest options in 60 of the state’s 64 counties. Citing also that the state has yet to import Canadian drugs four years after passing a bill to allow the practice, he complained that “everything the first floor (where Gov. Polis’ office sits) touches in the world of health care and health insurance is a failure.”

Sponsoring Sen. Dylan Roberts, D-Avon, defended the Colorado Option, however, noting that 63 of 64 counties now have multiple health-insurance carriers offering plans on the exchange and pointing out that 38,000 Coloradans are enrolled in option plans. The plans are in year one of a three-year rollout and strengthening the state’s ability to hold their costs down is about giving people choices they haven’t had, he said.

“This is about humans getting the security of health insurance, so they can get to the doctor when they need to,” Roberts said on April 24. “It is working as intended, and HB 1224 makes improvements to the program.”

Colorado state Sen. Dylan Roberts speaks on the Senate floor in April about his bill regarding the Colorado Option insurance plans.

Insurance mandates

Legislators also passed a slew of bills mandating new health-insurance benefits, including $60 price caps on epi-pens, required coverage of abortions, 12-month fills of contraceptives and provision of drugs for severe mental illness without step therapy. This came despite a 2020 signing statement issued by Polis that he would be disinclined to sign future legislation creating new insurance mandates because of their effect on the cost of health insurance.

Colorado Association of Health Plans Executive Director Saskia Young said insurers’ frustration is not with the underlying policies of the mandates but with the lack of discussion about how they are giving targeted breaks but driving up the cost of plans for everyone. Senate Bill 195, which CAHP is asking Polis to veto, would alone add $96 million to Colorado insurance costs because it incentivizes use of high-cost brand-name drugs in how it requires insurers to account for discount coupons from pharmaceutical companies to help patients buy drugs, she said.

“Premiums are like baking a cake. There are many ingredients that go into them,” Young said. “There just needs to be understanding about that.”

Focus on Pharma costs

Several bills took aim too at bringing down pharmaceutical prices, including one Polis already has signed, HB 1201, that bans pharmacy benefit managers from charging health-plan customers more for drugs they purchase than the PBMs pay to the pharmacies supplying them. But the bill, signed by the governor earlier this month, that most worries the industry is HB 1225, which seeks to expand the duties of the nascent PDAB.

As created in 2021, that advisory board was given the ability to study prices that manufacturers charge for drugs and to cap costs charged in Colorado for as many as 12 drugs a year before the PDAB was to sunset in 2026. But HB 1225 extends the board for another five years and allows it to consider more caps on more drugs, though not for an unlimited number and not for generic drugs, as the bill originally envisioned.

Colorado state Sen. Sonya Jaquez Lewis discusses her bill to expand powers of the Prescription Drug Affordability Board in the Senate.

Co-sponsoring Sen. Sonya Jaquez Lewis, D-Boulder, noted that both Republican and Democratic states are putting together PDABS to deal with escalating drug costs. And co-sponsoring Sen. Janet Buckner, D-Aurora, said caps are necessary at a time when people are cutting their pills in half because they can’t afford to fill their prescriptions as often as needed.

“I am very excited about this board coming together to reduce the price of prescription drugs,” Sen. Jeff Bridges, D-Greenwood Village, said during Senate debate on April 24. “I would like it to be faster. However, I would rather them ready, aim, fire than ready, fire, aim. And I am so glad for the care they are putting into this process.”

Some health-care bills remain in limbo

But Republicans like Smallwood lambasted both the idea of fixing prices on drugs and giving more time and power to a board that’s spent $1.3 million since its creation without taking a single action yet.

And Jennifer Churchfield – co-chair of Front Range PharmaLogic, an organization that promotes Colorado bioscience and biopharma to business and economic-development groups — said the impact of whatever price savings PDAB produces will be offset by manufacturers that choose to discontinue sales of certain drugs in Colorado if they can’t charge above a set price point. That could have a far more destructive effect on state residents’ health than costs that are perceived as being too high, and HB 1225 will only grow the number of drugs that could become scarce in this state, she said.

“People aren’t going to sell their products here if they aren’t going to get reimbursed for them,” Churchfield said. “Where is the concern about diminished patient care and accessibility to life-saving medication?”

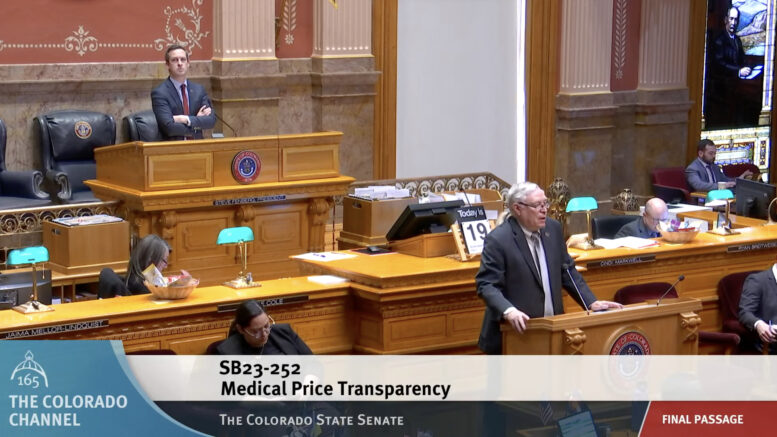

Among the aforementioned health-care bills, Polis has yet to sign the hospital facility-fees bill, the epi-pens price cap or the requirement for 12-month contraceptive coverage, in addition to SB 195. He also has not said if he’ll sign another pared-down mandate, SB 252, that would require hospitals to post their Medicare reimbursement rates and adhere to federal price-transparency rules, with violations of those requirements set to become deceptive trade practices that can be targets of lawsuits.