Members of an interim legislative committee studying ozone pollution are focusing more on the idea of increasing modeling and measurement of what are considered minor sources of pollution — a move that could ramp up regulation particularly on oil and gas wells.

A series of probes into this area by committee members over their past two meetings comes as oil and gas companies have been pleading their case that they are a small part of the overall emissions that have led to the ozone problem along Colorado’s Northern Front Range. Instead, they and officials from resource-rich Weld County have suggested that the state put more efforts into cutting two other sources of emissions — vehicles and lawn and garden equipment.

The committee is slated to meet another two or three times before the end of the year, and it won’t be able to propose bills as a committee — a concession that was made by sponsors of the bill that created the interim group to get it passed. But it’s very likely that some of its members will sponsor bills individually to ramp up regulations on emissions-producing sectors, which makes the conversations that have occurred in the past month significant as more groups are calling for legislators to do something.

“Local communities across the region are working very hard,” said Jacob Smith, executive director of Colorado Communities for Climate Action about city- or county-wide emissions modeling efforts that are underway. “The challenge is that we need state-level action as well.”

Existing modeling and monitoring

At a Sept. 22 meeting, many of the questions posed by committee members to federal and state officials revolved around which emitters are required to model and then to measure their output. Sergio Guerra, deputy director for stationary sources for the Colorado Air Pollution Control Division, said the need for modeling in based on conditions such as the dispersant characteristics of an emitter’s smokestacks, the proximity of disproportionately impacted communities and the background concentrations of pollutants that already exist.

Two years ago, the APCD started an informal process where its permitting team talked with its modeling team and began examining more applicants for their potential need to model emissions — a modeling process that oil and gas officials have described as lengthy and costly. After examining 18 applicants and requiring modeling from 16 of them in 2021, the team examined 480 applications and require modeling in 62 of them in 2022 and upped those numbers to 606 applications and 76 required models in 2023, Guerra said.

Colorado state Rep. Jennifer Bacon speaks on the House floor during the 2023 legislative session.

But Rep. Jennifer Bacon, a Denver Democrat and chairwoman of the committee, questioned whether requiring modeling of roughly 12% of studied applicants represents a strong enough effort to bring the Northern Front Range out of nonattainment with federal ozone standards. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency designated the area as being in severe nonattainment of those standards, mandating permitting for smaller sources of pollution and requiring drivers buy more expensive reformulated gasoline in high-ozone summer months beginning in 2024.

Ozone and emissions concerns of watchdog organizations

Environmental groups like Earthworks say that even when modeling is mandated, the state will rely on calculations in that modeling to demand source-specific emissions-control measures more than it will examine measurements of actual emissions from sites. Andrew Klooster, a Colorado field advocate for the national organization, noted that producers of emissions are left with the task of reporting emissions because state agencies don’t have the capacity to be taking measurements, and that creates its own issues, he said.

“When you’re relying on the industry to do this voluntary self-enforcement, sometimes you run the risk of things slipping through the cracks,” Klooster said.

Finally, Klooster and environmental officials with several local governments noted that pre-production activities on oil and gas wells, such as fracking, are considered temporary emissions sources and not subject to the same level of regulations — a determination they questioned. A federal appeals court last month ruled that the state improperly approved an air-quality improvement plan in December that did not account for those temporary emissions and must reconsider how to calculate them, according to the Denver Post.

Committee Democrats have not suggested specific ways to address the issues that they and environmental groups are highlighting. But at an Oct. 13 committee meeting, Lafayette City Councilman Tim Barnes suggested the Legislature eliminate “loopholes” in the air-quality permitting process, improve transparency around air-quality modeling data and direct the state to adopt critical control measures.

Pushback from oil-and-gas advocates

While so much energy continues to be focused on permitting activities that will affect oil and gas operations, though, several committee Republicans, officials from Weld County and representatives from oil-and-gas industry organizations warn that focus is too narrow.

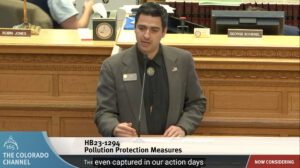

Colorado state Rep. Gabe Evans speaks against HB 1294, the bill that created the interim legislative committee on ozone issues, in the House in April.

Christy Woodward, Colorado Oil & Gas Association senior director of regulatory affairs, told the committee that oil and gas operations account for 3% to 8% of emissions at the 16 monitoring stations in the nonattainment area stretching from Douglas County to the Wyoming border. Satellites have tracked methane emissions as falling 72% over the past two decades, she noted, while Rep. Gabe Evans, R-Fort Lupton, cited NASA data that ethane and other pollutants also are down more than 50% in that time.

Other source of man-made emissions — including light-duty vehicles and gas-powered lawn and garden equipment, which have garnered an increasing focus from state regulators — account for 29% of emissions along the Northern Front Range, Woodward said. Yet an executive order issued by Gov. Jared Polis earlier this year focuses again on one industry, requiring oil and gas producers along much of the Front Range to cut nitrogen oxides 30% by 2025 and 50% by 2030, she noted.

Wider net needed for ozone reductions?

Annareli Morales, the environmental health specialist for Weld County, suggested to committee members that in addition to allocating consistent and sufficient funds for air-quality analysis, they need to attack other sources of emissions in a more aggressive way. She recommended legislators incentivize local governments to electrify vehicle fleets, create more incentives to transition from gas-powered lawn equipment and adopt a program like California offers that measures vehicle emissions at community events and then offers vouchers to lower-income individuals to get maintenance that will lower their emission levels.

“I’m focusing on these two because I don’t feel these two have had as much attention,” Morales said of the transportation and lawn-and-garden sectors.

A lawnmower sits in a yard in the Denver metro area.

Woodward also pushed back on intimations from some legislators that the Colorado Energy and Carbon Management Commission rubber-stamps oil-and-gas drilling permits and needs to reject more of them. She pointed to a revamped process, developed since passage of a 2019 bill bolstering oil-and-gas regulations, that requires 500-page applications to multiple state and local agencies as well as lengthy review processes that can stretch more than two years when modeling is required.

Current permitting process

CECMC Director Julie Murphy noted that the changes in the law have allowed commissioners to require more out of applicants, and she pointed to changes on specific projects that have cut the number of wells and the use of some high-emitting equipment before permits were OK’d. She noted in September that through these processes, operators have committed to plugging 803 wells, decommissioning 569 oil tanks and reducing about 32,000 annual vehicle trips to and from drilling sites.

“This upfront process is a lot of the reason why CECMC doesn’t deny a lot of permits,” Woodward said. “This is a very robust process.”

The next interim committee meeting is scheduled for Nov. 8.