Colorado legislators may consider creating a program that helps owners of the oldest, most-polluting commercial trucks to trade them in for new vehicles — a rare emissions-reduction effort from the state that would be driven by incentives rather than regulations.

But the proposed bill, which the Transportation Legislation Review Committee directed staffers to draft a copy of on Tuesday, would have to survive already brewing objections from environmental groups who want the state only to fund electric vehicles.

Several other states, including California and Texas, have a version of this commercially focused “cash for clunkers” program that is being advocated primarily by the Colorado Motor Carriers Association and the Colorado Wyoming Petroleum Marketers Association.

The idea behind it is that 75% of emissions from diesel vehicles in this state come from just 25% of trucks — those older vehicles typically owned and operated by smaller companies that struggle to find resources to upgrade. And these are the folks least likely to invest in electric trucks because of concerns about the weight their batteries will add to loads and their lack of near-term access to charging stations, meaning their best move is a switch to newer, less-polluting gas vehicles, advocates say.

What the bill would do

An older truck spews smoke.

On Tuesday, TLRC members voted 16-4 to draft a bill that would create a new “scrappage” program in the Clean Fleet Enterprise — an enterprise funded by $20 million in annual fees on food and package deliveries — awarding up to $2 million in grants per year. Owners of commercial trucks made before 2010 could get grants of as much as $50,000 to buy a gas-powered or alternative-fuel truck made in 2018 or later — dates that reflect changes in federal law that required much lower-emissions trucks than in the period before.

The emissions cut could be significant, as removal of one pre-2010 truck would equal the removal of 10 to 60 post-2017 trucks based on improved emissions and fuel technologies, said Grier Bailey, executive director of the CWPMA, a gas-station industry group. California instituted a program to remove older commercial trucks in 1998 and scrapped 68,696 vehicles as of 2020, reducing nitrous oxide by 198,417 tons and particulate matter by 7,343 tons, he noted.

“We think reducing emissions, in terms of NOx and PMs and even greenhouse gases, it’s more important to reduce those as soon as possible and remove those vehicles,” said Greg Fulton, CMCA president and a member of the Clean Fleet Enterprise board. “This is one of those strategies that can accomplish a great deal, essentially making things cleaner and safer in a much shorter time. And the way it’s structured, there would be no additional cost to those companies.”

Regulations have guided emissions cuts so far

The voluntary nature of the proposed program and its lack of mandated costs to employers — they would have to buy new trucks and scrap old ones, though the grants could cover as much as 50% of that price tag — is a huge selling point for business leaders. Over the past three years, state regulators have imposed emissions-reduction rules on sectors ranging from oil and gas to commercial buildings and from manufacturers to lawn-and-garden-equipment users, adding billions of dollars in compliance requirements.

Most of the reductions are a direct response to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s declaration that Colorado is in severe non-attainment of federal ozone regulations. The excessive air pollution coming from high-ozone levels — linked partly to Colorado sources and partly to factors like regional wildfire smoke and natural ozone production — exacerbates respiratory conditions by making it hard for some people to breath.

Vehicles, including commercial trucks, cross a bridge on Speer Boulevard in Denver.

EPA officials would consider adoption of the program a measurable pollution-reduction strategy, which would help Colorado move from severe violation down to serious violation and to lower levels after that, Bailey told the TLRC. The designation for the northern Front Range, as an area of severe violation, has required the sale this summer of reformulated gas, which cost drivers in August 40 cents per gallon more than they would have paid to buy regular gasoline, he said.

Objections from environmental groups

This is not the first time that trucking and convenience-store leaders have suggested such a program. In a bill several years ago, they attempted to impose a fee on older trucks to fund the grant program, but the provision was stripped from a bill because of backlash from environmental groups, Fulton said.

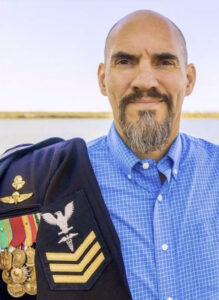

Juan Roberto Madrid is the sustainable communities program advocate for GreenLatinos.

What bothers many of those groups is the idea that the state would spend money to remove pollution-spewing vehicles from highways only to replace those with more internal-combustion-engine trucks that will continue to produce emissions, said Juan Roberto Madrid, sustainable communities program advocate for GreenLatinos. The Clean Fleet Enterprise has spent years awarding grants to move trucking and van fleets from gas consumption to charging, and paying for purchase of more gas vehicles would go against the spirit of those investments, Madrid said.

Not just that, but the proposed shift of $2 million annually away from other grantees could come as fuel gets dirtier and more polluting, he said. The EPA has moved to repeal an endangerment finding that is the basis for emissions regulations, and that removal would end mandates that commercial vehicles use a cleaner-burning gasoline/ethanol blend, thereby increasing emissions from trucks, Madrid said.

“The state also is offering incentives to build out charging infrastructure. So, why is the state doing that if they are going to do an incentive program … for buying trucks with internal combustion engines?” Madrid asked in an interview. “We’re keeping dirtier, gas-burning vehicles on the road for longer, and it’s not going to help us achieve attainment.”

Backers: This is the only way to scrap old trucks

Bailey, argued, though, that the choice for most trucking companies that would participate in the new program is not between buying new electric vehicles or new gas-burning vehicles but between getting new gas-powered trucks or sticking with their older vehicles.

The extensive batteries needed to power commercial trucks can add 6,500 pounds of weight compared to internal combustion engines, Bailey noted. With the federal government limiting the weight of vehicles on interstate highways to 80,000 pounds and most companies working to maximize loads, this limits electric trucks to carrying loads that are 8% lighter. And that puts those companies at a financial and operational disadvantage, Bailey said.

Most of the companies using these older, higher-emitting vehicles have small fleets — often five trucks or fewer, the kind of companies that don’t even belong to an industry group like the CMCA, Fulton noted — and can’t afford to be at any disadvantage. Also, many smaller companies focus on regional rather than national routes, which takes them to more rural areas where it is harder to find charging infrastructure, meaning they would have to go further out of their way and take more time to charge, Bailey and Fulton said.

“Market-driven” approach to emissions reductions

“I think it would show that we are taking a more data-driven and realistic approach to cutting emissions,” Bailey said of the proposal. “There are market-driven ways to do this. And simply because you want EVs all the time doesn’t mean that can happen.”

Bailey noted that while the Clean Fleet Enterprise has awarded $34.5 million in grants to acquire 177 electric trucks (which tend to cost twice as much as gas-powered trucks) over the past two years, production delays have left many of those orders unfulfilled. Manufacturers have delivered just 23 vehicles while 53 grants have been terminated or withdrawn, meaning that while the state is doing just what it promised with the enterprise, the dearth of electric-truck production is stalling planned emissions cuts, he said.

While the end results of the grants for larger commercial vehicle replacement have come more slowly than desired, that is not reason to turn away from the premise of using the fee revenues to get electric vehicles onto Colorado highways, Madrid retorted. Also, the enterprise could look to put more money toward electrification of smaller commercial vehicles, like vans, rather than redirecting it to internal-combustion vehicles, he said.

What happens next

Staffers are in the process of drafting five bills from the TLRC, including the trucking-grants measure, though only three of those bills can move forward as committee legislation — a culling process that is likely to happen when the TLRC convenes next month. If the committee fails to advance the bill, a legislator can offer it as one of their five allotted bills.

The bill proposal that the TLRC sent to drafting has bipartisan sponsorship — Democratic Sen. Kyle Mullica and Democratic Reps. Jacque Phillips and Alex Valdez have signed onto it along with GOP Sen. Byron Pelton. But its opponents notably include the chairs of both the House and Senate transportation committees, Democratic Sen. Faith Winter and Democratic Rep. Meg Froelich. And the Colorado Energy Office has been one of the biggest proponents for directing more transportation funding to electric vehicles and chargers.

“This is a worthwhile concept to be looking at,” Mullica said when he made the motion for the bill to be drafted on Tuesday. Time will tell if the concept of using more incentives to promote emissions reduction — both in the transportation sector and beyond — will gain the traction needed to advance.