Colorado’s labor battles escalated significantly on Friday, as the state’s largest unions filed a ballot initiative that would require private-sector employers to prove just cause before they could suspend or fire any workers.

The filing of Initiative 43 follows the Feb. 19 decision by Colorado’s title board to approve the wording of a proposed 2026 ballot initiative from the Independence Institute that would ask voters if they would like to make Colorado a right-to-work state. And both are moving while a bill to upend Colorado’s unionization-governing Labor Peace Act has passed the Senate and is scheduled for its first House committee hearing on Thursday.

This latest effort from labor — specifically, the AFL-CIO of Colorado, SEIU Local 105 and United Food & Commercial Workers Local 7 — isn’t tied directly to the fate of the bill or the Independence Institute initiative, Colorado AFL-CIO Executive Director Dennis Dougherty said. The union-funded National Employment Law Project is pushing “just-cause” job protections across the country, particularly in Illinois and New York City.

But the timing of its introduction certainly adds another twist to the battle that is going on inside and outside of the Capitol in labor leaders’ push to make it easier for private-sector workers to form unions. And especially with Independence Institute President Jon Caldara saying that the fate of his ballot initiative is tied to the outcome of Senate Bill 5, it raises the likelihood significantly that Coloradans could face an expensive ballot battle next year if business and union leaders don’t reach a deal on the Labor Peace Act.

Labor Peace overhaul proposal started the fight

“This is to protect Colorado’s workers. That is why we are bringing it forward,” Dougherty told The Sum & Substance in an interview on Friday. “I’ve traveled the country a fair bit over the past few months, and there’s an appetite for workers’ rights initiatives on the ballot.”

Since 1943, the Labor Peace Act has guided Colorado organizing efforts, requiring two elections — one for workers to unionize with a majority vote and a second that requires 75% approval for unions to be able to take negotiating fees from all employees’ paychecks. Business leaders have said the unique rules give Colorado a leg up on the 23 states that require union membership for workplaces that vote to unionize and protect the finances of employees who don’t want to organize unless a large majority of coworkers vote otherwise.

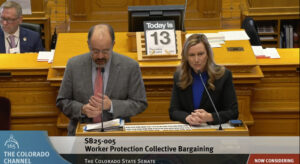

Colorado Senate Majority Leader Robert Rodriguez and Sen. Jessie Danielson speak for their effort to change the Colorado Labor Peace Act on the floor of the Senate in February.

But union leaders say the Labor Peace Act is an obstacle to organizing, and Democrats quickly pushed a bill through the Senate on a party-line vote that would eliminate the second election and allow union-security fees to be collected upon unionization. The bill is expected to pass the Democrat-heavy House as well, and Its fate would then come down to Democratic Gov. Jared Polis, who has threatened to veto SB 5 unless business and labor leaders come to a compromise agreement, which they haven’t yet.

Saying that “80 years of labor peace is about to be unraveled,” Caldara submitted a constitutional amendment that would prohibit workers from having to pay any fees or dues to a labor organization to work at any company in Colorado. This proposal mirrors laws in 26 right-to-work states in which employees can unionize but unions cannot compel membership or the payment of negotiating fees from anyone — states that all have lower rates of private-sector unionization than Colorado’s 6.9%.

Issue of just cause complicates other efforts

If business leaders agree to a deal on SB 5 or if Polis vetoes the bill, Caldara said he won’t move forward with his ballot measure. But if the governor signs a bill against the wishes of the business community, Caldara believes that fundraising for the right-to-work initiative will be “relatively easy” from business interests who do not want to see further erosion of the state’s business friendliness.

Independence Institute President Jon Caldara presents his right-to-work ballot initiative to the Colorado title board in February.

“This is not a fight I really want to have. This is a huge, expensive fight. And I’m not going to be the first to poke the bear. But if the Legislature messes with the Labor Peace Act, we will go to the mattresses,” Caldara said. “I think it fares well at the ballot … I think Colorado is not beholden to the labor unions.”

Now, however, the unions have a potential counter ballot measure, and Dougherty isn’t willing to say he will stop their efforts if Polis signs SB 5 or if Caldara holds his initiative. And this new initiative could have repercussions far beyond an overhaul of the Labor Peace Act.

What the new initiative would do

The just-cause initiative would require companies with at least eight employees to justify any suspension or discharge of a private-sector worker in writing to that worker within seven days of their action. Workers employed at the company for at least six months who believe they were disciplined or let go without cause could file a civil lawsuit seeking reinstatement, back pay, front pay, attorneys’ fees and “any other equitable relief the court deems appropriate.”

While Colorado employers are prohibited from discriminating against workers for public-policy and other statutory reasons and in protected classes based on factors like their race, gender or disability status, they otherwise can terminate employees with or without a reason. Requiring just cause would create vast new litigation possibilities for workers unhappy with their dismissal and introduce a great deal of subjectivity even in the reasons that employers may cite for terminations.

“This would be a major change. It would certainly open an employer to threats of lawsuits from an employee who is terminated,” said Dan Block, an attorney and employment-law expert with Robinson, Waters & O’Dorisio P.C. “Even if the employer clearly hasn’t discriminated based on protected class or other reasons protected by law, now you as an employer would have to establish that you terminated for good cause.”

Dan Block is a shareholder at Robinson, Waters & O’Dorisio.

How to establish just cause

The ballot initiative outlines seven reasons that employers could cite as just cause for a suspension or dismissal:

- Substandard performance of assigned job duties following notice and an opportunity to cure;

- Material neglect of assigned job duties;

- Repeated violations of the employer’s written policies and procedures relating to job performance;

- Gross insubordination that affects job performance;

- Willful misconduct that affects job performance;

- Conviction of a crime of moral turpitude; or,

- Discharge or suspension due to specific economic circumstances that directly and adversely impact the employer and are documented by an employer in written notification.

Polling shows that three-quarters of Coloradans support just-cause job protection, Dougherty said. And state residents’ uneasiness about job insecurity is being heightened now by the mass federal layoffs that make many workers realize that they don’t have the legal protections that they thought they might, he said.

Who would and wouldn’t be subject to requirement of just cause

Colorado AFL-CIO Executive Director testifies as part of a panel supporting the Worker Freedom Act in March 2024.

“The reason for submitting this initiative starts with Colorado workers having a better expectation around having workplace protections that prevent them from being fired without a valid reason,” Dougherty said. “People believe that they have just-cause rights. They’re shocked that they don’t.”

While the federal layoffs may have riled workers, the initiative would apply only to private-sector workers, exempting employees of federal, state and local governments except those working for the University of Colorado Hospital Authority and the Denver Health and Hospital Authority. Asked why government workers were exempted from protection in the proposal, Dougherty said he’s not sure state law can supersede federal workforce law, and he added that other just-cause statutes similarly have only applied to the private sector.

New York City in 2019 passed a just-cause law specifically for restaurant workers, but the only state to have put anything like Initiative 43 into place was Montana, in 1987. That law was amended in 2022, and its number of exemptions has made it workable for state businesses, said Greg Roadifer, president of the Associated Employers of Montana.

Montana law has had mixed impact

Its provisions for just cause, he explained, include unsatisfactory job performance, inability to perform the job, dishonest behavior and economic reasons. And in a provision that mirrors one in the proposed Colorado initiative, awards are required to subtract any amount of pay that experts say the dismissed worker should have earned by using reasonable diligence to find a job with another company.

However, economic-development leaders in Montana have cited the law at times for hurting the state’s business-friendliness reputation and its ability to attract corporate expansions or relocations, Roadifer said. And there are a “reasonable amount of lawsuits” filed against employers by workers who believe they have not met the just-cause standard, he added.

The actions of the Colorado Legislature, Polis and the Independence Institute, in conjunction with business leaders, will determine which, if any, labor-focused initiatives go before voters in 2026 on a ballot that already will be crowded with gubernatorial and U.S. Senate races. But it’s clear that what began as a debate about the second-election provision in the state’s Labor Peace Act has grown into a multi-faceted fight on workers’ protections that could impact every private-sector employer in the state.