When Colorado state leaders discuss disproportionately impacted communities and the regulatory protections that should be given them, they rely on a tool known as EnviroScreen that measures socioeconomic and environmental conditions.

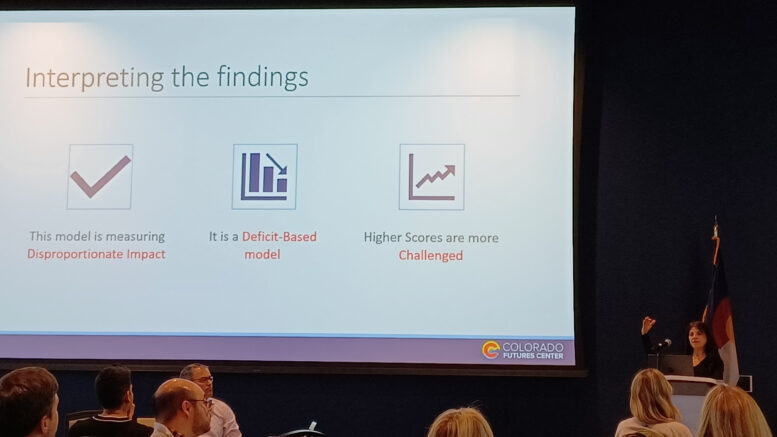

On Tuesday, however, the Colorado Energy Foundation and the Colorado Futures Center at Colorado State University will roll out the latest version of a program it believes also should factor into such discussions — its Colorado Disproportionate Impact Indicator, or CODI. The organizations behind that tool don’t believe it should supplant EnviroScreen, but they’d like it if state leaders use it to supplement the use of the that existing tool to look at which communities suffer disproportionate impacts from different angles.

“What we’re doing is saying: Here’s another lens on the concept of disproportionate impact,” said Phyllis Resnick, lead economist and executive director of the Colorado Futures Center. “We don’t have the authority to change the definition the state uses. But we hope this can shine a light on other issues that impact the ability of a community to thrive.”

Measuring disproportionate impact

Colorado law defines a disproportionately impacted community as a census block group where at least 40% of households are below 200% of federal poverty level, 40% of residents are not white or 50% of households spend more than 30% of income on housing costs. But the DIC definition also considers environmental impacts, including whether a census block has a history of environmental racism or experiences environmental health disparities, and whether it has a Colorado EnviroScreen score above the 80thpercentile.

EnviroScreen, developed by CSU in 2022 for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, aggregates data from 35 sources to identify communities experiencing greater environmental health burdens or facing higher environmental health risks. It is the basis for determining if the community meets the “cumulative impacts” prong of state environmental-justice law, which combines its findings with socioeconomic impacts and gives greater protections to that area when businesses apply for air-quality permits.

CODI takes a wider approach to defining a DIC by considering 12 factors: Classrooms, early childhood education, healthcare facilities, household wealth, environment, economics, employment, social measurements, food insecurity, transportation access, public health and housing. And it measures them over a census tract, which at roughly 4,000 people typically encompasses a larger population than a census block group, which is more geographically based and could have as little as a few dozen inhabitants.

A supplement, not a substitute

CODI, launched in late 2023, was never positioned to be an alternative to EnviroScreen; indeed, it uses EnviroScreen data to help determine the environmental exposure score in its calculations. But its creators believe it can paint a fuller picture of community needs when they also are able to consider factors ranging from classroom churn to employment levels to Internet access.

The tool is available to nonprofits and public agencies on its website, and about half of its registered users are 501(c)(3) organizations looking to understand more granularly which populations are in the greatest need of their aid and how they can deliver services to them. Colorado Food Bank, for example, examined areas’ food insecurity and layered it with other challenges to the population in areas it serves, and Energy Outreach Colorado used it to identify strategic partners in places with low internet connectivity, Resnick said.

CODI 2.0 will use updated data from the American Community Survey and from other sources like the Colorado Department of Education, Resnick said. Colorado Futures Center and the Colorado Energy Foundation, which funded the creation of CODI, have worked with a coalition of social-service providers to figure out how to make the tool most relevant to the groups in need.

EnviroScreen praised for influencing protections

EnviroScreen also got a makeover late last year, updating its data and incorporating new health indicators. And in a change backed by business leaders who find themselves dealing with regulations influenced by EnviroScreen scores, its operators updated its distance-weighted buffer methodology to better reflect the impact of drilling or mining on communities based on where pollution point sources are in proximity to homes.

Environmental advocates have lauded EnviroScreen during many Colorado Air Quality Control Commission rulemakings, saying that it allows them to empirically prove some communities have been harmed disproportionately and need more regulation. The AQCC gave special protections to DICs while developing rules pertaining to permitting for carbon capture and sequestration, emissions controls for oil-and-gas pipelines and general air-quality permitting, among other areas.

CODI proponents still believe, however, that the sources aggregated into the EnviroScreen score often are more appropriate for urban corridors than for some of the state’s more rural areas. Colorado Energy Foundation Executive Director Sara Reynolds said she’s heard that argument particularly from Western Slope leaders, who find regulators placing increased restrictions on oil-and-gas operators in DICs despite that fact that those DICs are determined wholly by the lower income of those areas rather than environmental threats.

More data points and their influence on disproportionate harm

The maps of DICs developed through CODI methodology aren’t wildly different than those that use EnviroScreen as a determinant. The San Luis Valley, southeastern Colorado, the Eastern Plains and parts of Denver are the most disproportionately impacted, while Pitkin and Routt counties, the Boulder/Broomfield region and much of south metro Denver — places defined by higher wealth — are least impacted, Resnick explained during the public rollout of the tool in December 2023.

But CODI can go beyond saying an area suffering disproportionate harm is poorer or more polluted and define it as one that suffers from a lack of public-transportation options or a low percentage of voting or poor teacher pay (which in turn can lead to high job turnover), Reynolds and Resnick said. And in that, it can detail the kind of help that the state or nonprofits need to give to an area, rather than declare in blanket fashion that all DICs most need greater environmental protection.

Reynolds said she has talked with some legislators about them running a bill in 2026 that would allow state regulators to consider CODI data to supplement EnviroScreen findings as they consider how best to serve lower-income areas of the state. That ability will be particularly needed if Congress does indeed make major budget cuts and send less money to states, which would require Colorado leaders to use more precision in where and how they spend more limited funding.

“This is a tool that tells the complete story of communities,” Reynolds said. “I think more information that helps us better understand our communities and better serve them should always be a welcome addition to any conversation.”