Coloradans will spend the next five months discussing the tax implications of Senate Bill 303. But an under-the-radar law that served largely as a companion bill to that measure could bring more definite commercial property-tax relief — at least in the opinion of some of its supporters.

SB 304, sponsored by Democratic Sens. Chris Hansen of Denver and Steve Fenberg of Boulder, establishes in law the factors that county assessors must consider when determining the actual value of a property. The intent, said officials from Colorado Concern who pushed for the new law, was to ensure that properties are valued based upon their current use rather than on a highest and best use that can inflate the value of commercial properties in particular.

Some officials, including the only former county assessor who now serves as a member of the Legislature, said that the bill is likely to have little effect, as few if any assessors consider highest and best use when determining property value. But others who study the assessment process, including one prominent Denver businessman who has protested assessments on his night club, say that overzealous assessment of aging urban properties that are not being turned into 10-story apartment buildings is a real threat to the ability of long-time businesses to remain open.

“(SB) 304 gives property owners protection they have not had before from an assessment process that is overburdened by complexity and weak transparency,” Colorado Concern President/CEO Mike Kopp said in an interview. “Most importantly, it will require that assessors place a value on the building as it is, not as it could be.”

The other property-tax bill

Gov. Jared Polis signed SB 304 last month at the same ceremony where he inked into law SB 303, overshadowing a bill that received bipartisan support with one that is clouded in controversy. Passed on the final day of the 2023 legislative session, SB 303 reduces property assessment rates and limits growth of assessed values over the next 10 years — if voters in November approve Proposition HH, which would raise the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights cap on state spending annually to fund backfills for local governments over last property-tax revenue.

Colorado state Sen. Chris Hansen discusses his property-tax relief bill on the Senate floor.

SB 304, which earned one sentence in a two-page news release from Polis about signing the two bills, sets out five conditions for an assessor to consider in establishing property values. It specifies current use as the first condition, following it with existing and other government land use, multi-year leases or other contractual agreements affecting property income, easement and reservations of record and, lastly, covenants and restrictions of record.

Graham Anderson — a senior analyst with research and consulting firm Anderson Analytics, which does fiscal-impact studies for governments on new developments, among other things — said he’s seen “rather shocking commercial valuations” in urban Front Range counties recently. And he attributed that in part to a 1988 Colorado Supreme Court decision that failed to define market value of a property, allowing assessors to consider conditions including potential future changes to the property.

How are assessments done?

Assessing to such “highest and best use” — a trend that Anderson said he’s seen increasingly as a greater percentage of properties are sold for speculative reuse value, like an abandoned liquor store he found that went for $700 per square foot — hurts older properties in boom areas. As nearby landowners may sell old cafes or historic one-story buildings for apartments or office buildings, even owners who didn’t do that saw assessments grow 20% to 40% this year because of sales of area land that went the redevelopment route, he said.

Andrew Feinstein, owner of the Tracks nightclub in an area of Denver’s River North Arts District that’s seen high-dollar development around it, noted that his assessed value rose from $7 million in 2015 to $11.7 million in 2017 to $20.4 million in 2019. He protested the 2019 assessment and got it knocked down to $14 million then saw valuation hikes to $19.2 million in 2021 and $30.3 million in 2023 despite little change to his property, saying that assessors were noting that so many other properties around him sold for so much higher.

“If you own property in the urban core, you get assessed for what you should be, not what you are,” Feinstein said. “At some point, you can only charge so much for your beer. With this ‘highest and best use’ valuation, assessors are forcing businesses to sell their property, whether they want to or not.”

“Interesting view of assessors”

But Rep. Lisa Frizell, a Castle Rock Republican who formerly served as the Douglas County assessor, said she considers the bill to largely be a “nothing burger” because she doesn’t know of other assessors who are tying actual value to the highest and best use of a property. Frizell originally was a co-sponsor of the bill, which also requires more transparency on the appeals process from assessor’s offices, but she pulled her name off it and later voted against it because she felt it painted an incomplete picture of what assessors do.

Assessors don’t value for highest and best use because they are required to classify the property each year and, in doing so, value the property as it’s currently being used, she said. Nor do they automatically deny commercial appeals, as seemed to be implied via a section in the bill that requires counties of 300,000 population or greater to use an alternative protest and appeal procedure that gives assessors more time in reassessment years to review appeals, she said.

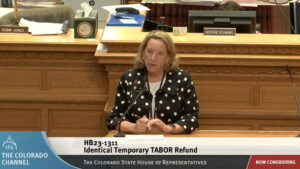

Colorado state Rep. Lisa Frizzel discusses a bill on TABOR refunds that is tied to a controversial property-tax bill in the House.

“The folks at Colorado Concern have this really interesting view of assessors. And it’s not a positive view, and it’s not always a realistic view,” Frizell said in an interview. “We had to kind of agree to disagree on what is actually happening.”

A continuing debate on property tax

The dual efforts of SB 303 and 304 come after spiking property values have led to assessments rising an average of 30% to 40% in most counties, threatening the ability of longtime business owners and homeowners to afford to keep their homes or commercial land. Proposition HH promises businesses with $1 million property valuations average tax savings of $12,402 over the next five years — but only if they agree to a compounded raise of the TABOR cap that could eliminate TABOR refunds in years of excess revenue collection in a little more than a decade.

Anderson said that suburban counties aren’t seeing the spike in commercial valuations that urban areas are, and he attributed that to the redevelopment driving speculative land sales and leading some assessors to boost valuations of older, often mom-and-pop businesses. That information comes from numbers attributed by the assessor’s offices, and he believes that SB 304 will clarify what case law has not and will lead to current-use-only assessments.

“One of the biggest things I’m hearing (from commercial property owners) is ‘My rent rate didn’t go up 30% to 40% over this period,” added Anderson, who has worked with Colorado Concern on efforts to research property taxes. “I think we kind of have had a perfect storm.”

A Denver District Court judge last week ruled against a challenge to Prop HH going on the November ballot, setting it up for a statewide vote. Advance Colorado, the fiscal-conservative watchdog that brought the lawsuit along with about a dozen local governments, has said it will appeal the ruling.