Colorado’s three-year-old Prescription Drug Affordability Review Board is reaching a major crossroads, as it is embarking on its first effort to set an upper payment limit for a drug at the same time that lawmakers are considering limiting the drugs that are within its reach.

One week ago, the board voted for the first time to declare a drug unaffordable — specifically, Enbrel, an autoimmune-disease medication whose price has risen nearly 1,600% since 1998 and cost Coloradans more than all but two other drugs in 2021. On Friday, it then voted to initiative the rule-making process to set a cap on the price that pharmacies can pay for Enbrel — a process expected to take about six months that will be the first creation of an upper payment limit in the United States.

The board also have voted twice since December to declare studied drugs not to be unaffordable — Trikafta, an expensive but highly effective cystic fibrosis treatment, and Genvoya, an HIV medication whose usage has fallen by more than two-thirds since 2018. The rejection of the label for Trikafta came only after massive backlash from both users of the “miracle” drug and some doctors who argued that doing so could threaten access to the drug by Colorado users and sentence them to debilitating lives.

Legislative pushback to PDAB deliberations

And so, Republican Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer of Brighton and Democratic Sen. JoAnn Ginal of Fort Collins authored Senate Bill 60, which would exempt orphan drugs such as Trikafta from PDAB consideration. Orphan drugs are defined federally as those taken by people with a disease that affects less than 200,000 Americans, and they get special tax credits and speedier regulatory reviews as well.

SB 60 on Thursday advanced out of the Senate State, Veterans and Military Affairs Committee on a 3-2 vote, but its fate before the Senate is tenuous, as many patient-advocacy groups said it would exempt too many drugs. Sen. James Coleman, the Denver Democrat who joined with committee Republicans to cast the deciding vote, even said that he was backing the bill to continue its discussion before a larger body but that he would be voting “no” against it on the floor.

Colorado state Sen. James Coleman addresses the Senate in January.

Underlying the discussions that both the Legislature and the PDAB have been having in recent months is the question from both advocates and dissenters on whether it is fulfilling its purpose.

Has the PDAB process worked as intended?

Backers said its careful consideration of its first three price-reviewed drugs and decision not to take price-limiting action on two of them show it is threading the needle of trying to cut health-care costs without imposing arbitrary caps on drugs that don’t need them. SB 60 would eliminate two-thirds of medications under consideration for upper price limits — prescriptions that are used by 14,705 Colorado patients — and narrow the board’s abilities too much, argued Hope Stonner, Colorado Consumer Health Initiative policy manager.

“The findings today illustrated that the board’s work is very useful and very necessary,” CCHI Executive Director Mannat Singh said after the Feb. 16 deliberations on Enbrel and Genvoya. “PDAB is an opportunity to make meaningful policy choices that promote health over profit.”

But SB 60 proponents, including some prescribing physicians, said the debate over potentially capping Trikafta costs, which stirred cystic fibrosis patients across the state into asking the board not to take action on the medication, showed that even consideration of orphan drugs can have detrimental effects on the mental health of a vulnerable population.

Potential prescription-drug price caps sow fear

Over the past six months of board meetings, it’s become clear that many users of the subject drugs, even those who complain about their prices, believe that if Colorado limits what pharmacies can pay for them, manufacturers won’t sell the drugs in this state. Before the five PDAB members declared last week that Genvoya was not unaffordable several patients made that leap and warned their health was at great jeopardy in the event of an upper payment limit placement.

“I think that HIV should not be one of the categories for this program,” Michael Dorosh, a 37-year HIV sufferer, told the board. “If I stop taking my HIV drug, I die.”

Legislative Democrats pushed through a bill to create the PDAB in 2021 and then to expand the number of drugs it could consider (from 12 to 18) in 2024 while also extending its timeline. Knowing that Colorado was moving faster than any other state that had authorized such a board, they have said the state has a chance to lead nationally in the battle to force manufacturers to rein in prices or potentially lose a market.

PDAB appointees unanimously voted against declaring it unaffordable, despite its annual average of $8,907 in out-of-pocket payments, in part because of the discounts that manufacturer Vertex offers to users. However, a significant number of users declared that the board’s consideration of using unprecedented power to deny reimbursement levels to a manufacturer that spent billions of dollars developing the drug was reckless and should make people question board functions.

Why another prescription drug is headed to a payment limit

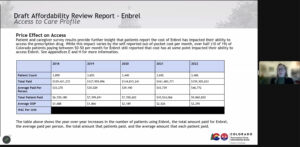

Lila Cummings, Colorado prescription drug affordability director, explains cost breakdowns for Enbrel to the Prescription Drug Affordability Review Board during a February meeting.

The board’s decision to declare Enbrel unaffordable did not engender a huge amount of controversy from the 3,406 patients in Colorado that take the medication. Board members noted that its average out-of-pocket annual costs rose from $1,688 to $2,295 just between 2018 and 2022, and Colorado Insurance Commissioner Michael Conway testified that state residents spent $159 million on it in 2022.

“The average out-of-pocket is high,” said Dr. Gail Mizner, PDAB chairwoman. “For people to be paying over $2,000 per year for one medication is high.”

But now the first-in-the-nation body will enter unchartered territory and will set a payment limit for that drug, which is likely to draw scrutiny even from those who have yet to defend Enbrel’s costs as a medication.

And the manufacturer’s reaction to that limit — as well as investors’ decisions on whether such a limit will curtail their funding of bioscience companies, a resounding fear of state industry leaders — will offer a better glimpse into exactly what impact the board will have on costs and whether more officials or fewer officials will seek limits to its power.