Supporters and critics of a Colorado board’s decision to consider price caps on life-sustaining drugs for patients with rare diseases have reached a détente after months of debate on whether it should ban any consideration of “orphan drugs” for greater regulation.

Senate Bill 203, which passed the upper chamber of the Legislature on a unanimous vote Wednesday, gives patients with these afflictions and the Rare Disease Advisory Council a voice earlier in the Prescription Drug Affordability Review Board’s process. Rather than requiring them to wait to chime in until the board decides to review the cost of a sparsely used drug, it mandates that the PDAB consider input from them — and consider whether a medication has orphan-drug status — at the start of its process.

That, acknowledged cosponsoring Sen. JoAnn Ginal, D-Fort Collins, is a “step back” from a previously introduced measure, SB 60, that would have banned consideration of price caps on any orphan drugs by PDAB. That bill set off fiery debate between health-care advocates and the takers and prescribers of those drugs on whether such price caps could lead pharmaceutical manufacturers to pull the drugs from the Colorado market and deal a huge blow to the health of patients.

Now, SB 60 is dead with the agreement of Ginal and cosponsoring Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer, R-Brighton, and SB 203 is on its way to a hearing in the House Health & Human Services Committee on Tuesday — and likely to Gov. Jared Polis’ desk. While debate continues to swirl around the nationally precedent-setting work of the PDAB, the compromise on orphan drugs appears to have produced a solution acceptable to all parties involved.

How the debate on orphan drugs came about

Colorado state Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer speaks on the Senate floor earlier this month.

“We believe this is what makes good policy — listening to those impacted and finding a collaborative way forward,” Kirkmeyer told the Senate State, Veterans and Military Affairs Committee during its initial hearing for SB 203 on April 18.

The fight over orphan drugs is a microcosm of the now-three-year-old debate over the first-in-the-nation creation of a board to review prescription drug costs and potentially set upper payment limits on them within the state.

In December, board members first considered — and rejected — the “unaffordable” label for Trikafta, a so-called miracle drug taken by cystic fibrosis patients that’s proven to restore their health and get individuals back to fully functioning lives. Even consideration of capping prices on the drug caused an uproar in the cystic fibrosis community — estimated to be between 450 and 700 Coloradans — as members feared having to leave Colorado or be reduced to repeated hospitalizations without the drug.

From there grew a debate over whether PDAB should consider limitations at all for “orphan drugs” taken by individuals with rare diseases that affect less than 200,000 Americans. Groups such as the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative warned that doing so would remove from the PDAB’s purview two-thirds of the drugs it now can consider for price caps, effectively neutering the board’s ability to bring down healthcare costs.

How the compromise was reached

While SB 60 passed its first committee by a one-vote margin, it did so only when swing-vote Sen. James Coleman, D-Denver, warned that he would not support it on the Senate floor, making its success seem precarious. So, Ginal and Kirkmeyer worked on ways to elevate the opinions of the rare-disease community as soon as the board might begin considering their medications and potentially avoid the stress of a showdown before the PDAB.

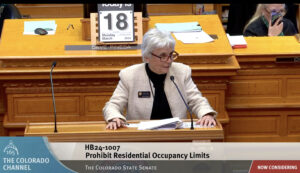

Colorado state Sen. JoAnn Ginal speaks on the Senate floor earlier this month.

“We heard loud and clear that patients with rare diseases, their families and their caregivers want the board to consider their voices earlier in the process,” said Kate Harris, Colorado Division of Insurance chief deputy commissioner.

While the orphan drug battle appears over, though, the board faces another potential obstacle in the form of a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of its very existence by the maker of a drug that faces an upper payment limit.

Orphan drugs just one controversy surrounding PDAB

After passing on declaring Trikafta unaffordable, the PDAB in February bestowed that label for the first time on Enbrel, an autoimmune-disease medication whose price has risen nearly 1,600% since 1998 and cost Coloradans more than all but two other drugs in 2021. The board is currently in the process of determining what the upper payment limit for the drug, taken by roughly 3,400 Colorado patients, should be.

However, drug manufacturer Amgen last month sued the state of Colorado, arguing that the 2021 law creating the PDAB conflicts with federal law and unconstitutionally interferes with its ability to make profits off its products, according to the Denver Post. In addition to creating an upper payment limit for Enbrel, the board now is in the process of determining whether two other autoimmune-disease drugs, Stelara and Cosentyx, are unaffordable.

Polis last year signed a law expanding from 12 to 18 the number of drugs that the PDAB could examine in terms of affordability, feeling the board is a critical tool in his multipronged efforts to save Coloradans money on health care. Now a court will decide if it’s a tool the state can continue to employ.